Language is a curious and revealing thing. Take the term ‘coral reef’. In Bahasa Indonesia, national language of the world’s largest island nation, the translation is batu karang, batu meaning ‘rock’. The word speaks of strength, solidity, uniformity.

Yet tropical reefs are spectacularly colourful in their diversity, and also among the most fragile and complex habitats on Earth. They’re not inert minerals – they’re very much alive.

Of Indonesia’s estimated 51,000 sq km of coral reefs, its eastern region alone comprises perhaps 60% of global hard coral species, around which shimmer more than 1,650 types of reef fish, as well as graceful turtles, lithe eels, tiny seahorses and shy octopuses.

This incredible biodiversity is replicated globally. Coral reefs occupy less than 1% of the ocean floor, but provide habitat for around 25% of marine life – an estimated one million species. A coral reef isn’t just pretty.

© GETTY IMAGES

Coral Catastrophe

Today, though, coral reefs are under threat. Since 1980, around 50% of tropical corals have been lost as a result of human activity and a crucial, too-familiar factor: climate change.

Large-scale coral bleaching events, caused by extended periods of elevated sea temperatures, were first recorded in the early 1980s. They have since increased in intensity, extent, duration and frequency.

The first global bleaching event recorded, in 1998, devastated 16% of the world’s coral reefs. Between 2014 and 2017, three-quarters of tropical coral reefs experienced heat stress severe enough to trigger bleaching.

Climate models project that, even if the average global temperature rise is limited to 1.5°C (a core long-term goal of the 2015 Paris Agreement), perhaps 70–90% of tropical coral reefs could be lost by 2100. If temperatures rise 2°C or more, less than 1% are likely to survive.

This isn’t just a tragedy for wildlife – it’s a disaster for us all. We’re increasingly coming to understand the value of the so-called blue economy: annual fishing revenues from coral reefs alone are estimated at US$6 billion.

But the real cost will be borne by the people who depend on the habitat for food, coastal protection and income.

Corals are colonies of polyps – tiny, sac-like invertebrates related to sea anemones. Reef-building species, which typically inhabit shallow tropical waters, secrete calcium carbonate to create hard exoskeletons.

But it’s a slow process: some reefs grow less than 1mm each year. These species obtain much of their energy – and colour – from algae commonly called zooxanthellae, which live within their cells in a symbiotic relationship: the coral provides dissolved carbon and nitrogen to the guest algae, which ‘fixes’ it into organic compounds via photosynthesis to ‘feed’ its host.

When sea temperatures rise (by as little as 1°C ), this relationship breaks down, prompting the coral to expel the algae. The coral loses its pigmentation – hence the description of ‘bleaching’ – and may die.

© TOM VIERUS / WWF-US

Reefs of hope

The good news is that some healthy coral reefs can resist bleaching. Corals can survive in this state for a short period, and are able to recover if water temperatures subside, obtaining new zooxanthellae from the water. Bleached reef structures can be recolonised by larvae produced by coral elsewhere. And not all reefs, nor all coral species within a reef, are equally exposed to the effects of climate change.

A 2018 study identified the areas of coral reef worldwide that are most likely to survive projected climate change, and that have the greatest capacity to regenerate degraded reefs. Some 70% of them are in seven countries in south-east Asia, the west Pacific, east Africa and the Caribbean.

Through the Coral Reef Rescue Initiative (CRRI), in partnership with Wildlife Conservation Society, Rare, CARE International, Blue Ventures, the University of Queensland, Vulcan Inc and national governments, we’re aiming to protect so-called ‘regeneration reefs’ so that they can seed others elsewhere – a kind of submarine Noah’s Ark. And that means tackling a range of local problems.

“It’s a delicate balance: lots of things need to align for coral to remain healthy,” explains Carol Phua, our global CRRI manager. “Water quality is critical, and often dependent on land vegetation. When coastal mangroves or rainforests are cleared – to make way for oil palm plantations, for example – rain washes soil downstream and into the ocean, where it settles as sediment on the reef and suffocates the corals.

“Illegal logging inland can cause mudslides that inundate reefs,” Carol continues. “And untreated sewage smothers coral with bacteria. Then there’s overfishing, which can tip the balance of species in the reef ecosystem, and bottom-trawling or fishing with explosives or cyanide, which can damage the reef structure.”

That’s a lot of challenges. But, together with the rest of our CRRI partners, we’re determined to overcome them and make the most of the chance to develop a blue economy. Securing local, regional and national support is crucial.

So we’re talking to politicians and authorities in the seven countries to help shape the legislation needed to protect the reefs, and evolve land and marine planning and management. This will also help inspire the investment needed.

The world’s most resilient reefs

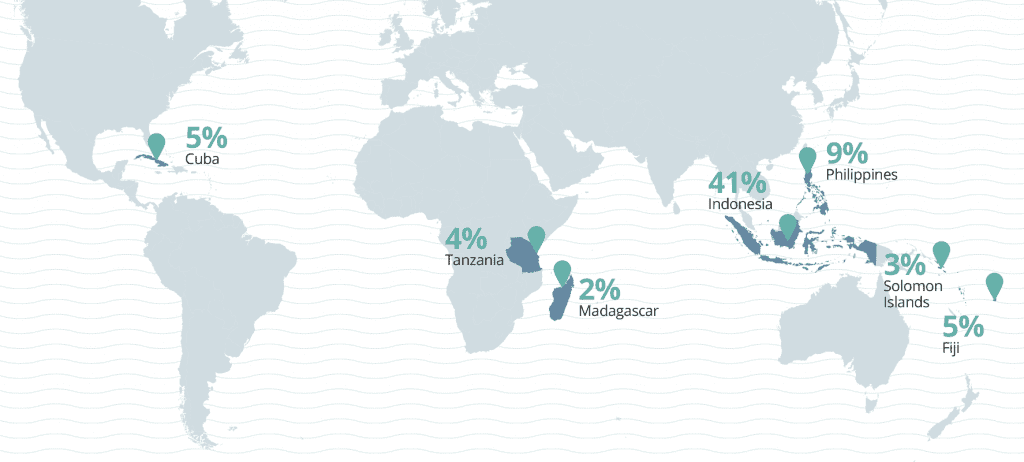

Together, just seven countries are home to 69% of the coral reefs that could survive climate change and help regenerate reefs around the world

A number of coral reefs across the tropics are relatively resilient to bleaching events caused by climate change, perhaps because local rises in sea temperature are less severe or typically coincide with cyclone seasons when exposure to sunlight (a contributing factor) is reduced.

In 2018, a study identified these resilient reefs and places where other, bleached coral reefs could be recolonised. Nearly 70% of these resilient reefs are found in just seven countries: Indonesia (41%), Philippines (9%), Cuba (5%), Fiji (5%), Tanzania (4%), Solomon Islands (3%) and Madagascar (2%).

Within these countries, the study identified 12 large reef sites covering 500 sq km or more, which have both a level of resistance to climate change and are connected to other reefs by ocean currents. Working with partners and local people in chosen areas within those sites, we’ll develop strategies for each location that support communities in safeguarding their reefs and livelihoods, in the hope of reseeding the coral reefs of tomorrow.

Safeguarding Reefs Together

Crucially, we’re also working with local communities to share their knowledge and understand their needs. “Our vision is not only to build and maintain the resilience of these reefs, but also the resilience of coastal communities who are dependent on these reefs,” says Carol. “So we’re targeting health and education. Climate change disproportionately affects women and children, so we’re particularly focusing on family planning, financial budgeting and education for women and children.”

Many communities living close to coral reefs struggle to overcome poverty. The reefs often provide their primary source of protein and income from fishing and tourism, but the lack of alternative livelihood opportunities can force them to rely too heavily on coastal resources.

“If your only way of making a living is fishing, or if you can only cut down mangroves to make charcoal, there isn’t a lot of resilience in your lifestyle,” explains Carol.

“If something goes wrong with the reef system, or when the mangroves are all gone, what else can you do? So creating other livelihood options is critical, for example through micro-financing small businesses in ecotourism or organic farming. And these need to be options that are wanted, not what we think we should offer: communities need to be owners of their own resources.”

One of the first sites that the CRRI is supporting is Fiji, home of the Great Sea Reef, known locally as Cakaulevu. At over 200km, it’s the third-longest barrier reef in the world. This marine biodiversity hotspot harbours around 40% of the known marine flora and fauna in Fiji, and supplies as much as 80% of the fish caught for the domestic fisheries industry. The communities here hold traditional rights known as qoliqoli to manage their local fishing grounds, including creating protected areas.

“For every Fijian brought up by the ocean, the first thing they see as they grow up is the reef,” explains Tui Macuata Ratu Wilia Katonivere, traditional leader of the province of Matuata on Vanua Levu. “To me, the Great Sea Reef is not only alive, it’s a source of sanctuary for us, the fish and the marine life.”

What do coral reefs do for us?

These beautiful ecosystems contain some of the greatest diversity of life on the planet. They also provide a host of essential services for people

FOOD

An estimated 275 million people live within 30km of reefs, with 500 million depending heavily on populations of reef fish as their source of protein and income.

PROTECTION

Coral reefs are natural barriers that protect nearly 200 million people from storm surges and tsunamis. They also protect seagrass beds and mangroves from being uprooted.

TOURISM

Coral reefs and their rich marine life are a big draw for international tourists, attracted by activities such as diving and snorkelling, who spend an estimated US$36 billion a year in destinations near to reefs.

MEDICINES

Corals are yielding compounds used to develop medicines that could treat conditions including cancer, arthritis, Alzheimer’s, heart disease, and viral and bacterial infections.

Yet, despite such reverence, Fiji’s reefs are threatened by climate change, pollution and overfishing. “Fiji is dependent on monoculture sugar-cane farming, which relies heavily on pesticides and fertilisers,” explains Carol. “The run-off causes damage to the reefs. So we’re hoping to encourage investment in organic farming and a shift to other crops, or even agroforestry.”

Meanwhile, some parts of the Great Sea Reef are commercially exploited for live reef fish, and illegal fishing has contributed to dwindling fish populations.

To understand the impact of these threats, we’re supporting an initiative to assess the health of the Great Sea Reef, as well as other critical habitats for wildlife and people that face similar threats in Kenya, Nepal and Borneo.

“The Biome Health Project aims to develop a field-based study system that provides insights into how nature responds to human pressures, and how conservation efforts can help reduce the effects of these pressures,” says David Curnick, a postdoctoral research associate at the Zoological Society of London, who leads the Biome Health Project marine work.

Hawksbill turtles

Parrotfish

Sharks

Pygmy seahorses

© GETTY IMAGES

Reef under pressure

In 2019, the project team, along with WWF colleagues in Fiji and the US, surveyed the Great Sea Reef. They used underwater photography and stereo dive-operated video cameras to build up an image of the underwater environment and assess the general health of the ecosystem, based on three critical parts of the reef: seabed (coral, algae, sponges), fish, and invertebrates such as sea cucumbers, giant clams and crown-of-thorns starfish.

The results reveal the percentage of coral cover, the coral species present, and the prevalence of factors such as bleaching or disease. We also trialled acoustic sound traps to record the noises made by ocean invertebrates. The more complex and intense the sounds, the more diverse the life on the reef is likely to be.

The team is still analysing the video footage gathered, but it’s already clear that fish abundance and diversity are highly variable across the reef. Though there is some evidence of coral bleaching, the Great Sea Reef has not experienced the mass bleaching events that have destroyed corals elsewhere.

In 2021, we aim to run further surveys and take a more detailed look at fishing methods in the area to measure their impact on the reef. The results will provide a ‘baseline’ to record the future health of the reef.

We’ll also develop a long-term reef-monitoring programme to help determine if the conservation activities being implemented are effective. And we’ll support the Fijian government with meeting its commitment to establish a network of marine protected areas to cover 30% of the country’s waters.

This is critical to ensure a healthy reef, as David observes: “Overfishing removes fish and invertebrates from the reef, which can enable fast-growing algae to take hold and outcompete coral.”

We have a unique opportunity to build a future for these ‘regeneration reefs’ in Fiji and elsewhere. But we need to act quickly. “Realistically, we have five years,” says Carol. “If we don’t secure these reefs within that time by sufficiently reducing the threats, there won’t be enough reef left for us to rescue.”

• This is an edited version of an article that originally appeared in WWF Action magazine in 2020.

Adopt a turtle

To help us protect even more of Fiji’s turtles, you can adopt a turtle.

More to explore

Make nature our climate hero

Nature can be one of our greatest allies in the fight against climate change. We’re calling for urgent action from governments to limit global warming to 1.5ºC – with the help of nature-based solutions