Hong Kong, 6 July: a busy day at Kwai Chung Customhouse, as customs officers inspect a shipping container newly arrived from Malaysia. At first all seems routine: the cartons are unloaded one at a time – each packed with frozen fish, just as it says in the paperwork. But it’s not the cartons that interest the officers.

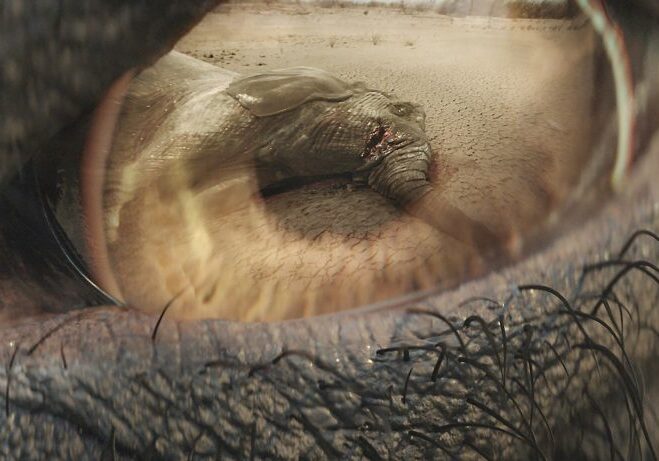

Sure enough, their worst fears are soon confirmed. Beneath the cartons, the container is piled high with elephant tusks. Even these experienced officers, working at the very hub of the world’s illegal wildlife trade, are shocked by the number. Altogether, the haul weighs in at a staggering 7.2 tonnes: the largest illegal ivory shipment seized in recent decades. More than 700 elephants have died for this. Arrests follow and vital intelligence is gleaned. But it’s a bitter-sweet moment.

“We’re finding smaller tusks in seizures because the big tuskers have all been poached,” says Tom Milliken, elephant and rhino programme leader of wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC, one of our partners. “The demand for ivory has increased so much that poachers are targeting any animal with ivory.”

Today the global illegal wildlife trade is estimated to be worth more than £17 billion and is thought to be the world’s fourth largest transnational crime. Its effects are devastating: an estimated 17,000 elephants are being poached in Africa every year for their ivory, while almost 10,000 rhinos were poached for their horns across Africa in the last decade.

© EDWARD PARKER / WWF

According to TRAFFIC, the current scale of this problem is enormous. “Between 2010 and 2017 we had six successive years of record ivory trafficking levels,” says Milliken, “which is extremely worrying.” He fears that despite efforts, including US$1.3 billion committed by the world’s leading funders to combating the illegal wildlife trade since 2010, the desired effect isn’t being achieved yet. “That’s the highest investment we’ve seen,” he explains, “and yet the statistics of what’s happening to wildlife on the ground are not moving enough.”

Illegal wildlife trade may now be driving some species to the brink. “We’ve already seen the Javan rhinos in Vietnam wiped out,” says Milliken. And it’s not only ‘A-list’ animals, such as elephants, rhinos and tigers, that are targeted.

“There’s a whole lot of species that still aren’t in the global imagination yet,” he adds, explaining how animals as diverse as hornbills, basking sharks, sea cucumbers and serow (an antelope-like mammal) are today being targeted. Recent data reveals that the most trafficked wild mammals are now pangolins: an estimated 117,000–234,000 of these elusive, insect-eating mammals were killed for their scales and meat between 2011 and 2013 alone.

WILDLIFE IN DEMAND

It’s a global problem, but today the core markets for the world’s illegal wildlife products are China and south-east Asia, while Africa suffers the greatest plunder. “Asia has come to Africa, as Asia has not lived sustainably with its own natural resources,” explains Milliken.

As this grisly trade casts its nets ever wider, it seems everything is up for grabs. Milliken recounts how breeding colonies of carmine bee-eaters, a bird prized for its colourful feathers, have been excavated from African river banks. Such stories, on top of the data, leave no doubt that we’re now in a crisis situation. “These last few years have been horrific,” he says.

Meanwhile, as well as desecrating the environment and driving species towards extinction, the trade destroys lives. Its corruption breeds further corruption. Communities are intimidated, livelihoods lost and, in extreme cases, civil conflicts inflamed. Those who intervene may risk everything. Between 2009 and 2017, around 740 wildlife rangers across the world lost their lives in the line of duty.

The trafficking of wildlife products is key to the illegal wildlife trade. It’s the supply line between poacher and consumer. Seizures of trafficked goods provide compelling evidence of how the trade is proliferating. Take rhino horn. From 2000 to 2005, 664 horns were taken in Africa for the illegal trade, with 173 subsequently seized. From October 2012 to December 2015, 8,691 horns were taken in Africa, with 890 seized worldwide.

The locations of such seizures help identify the trafficking routes. They have revealed, for example, that South Africa’s OR Tambo International Airport (26 rhino horn seizures alone) and Kenya’s Mombasa port are key smuggling conduits out of Africa by air and sea respectively.

They also reveal that many other countries, including Ethiopia, Indonesia, Qatar, Singapore and the UAE, serve as transit points. In May 2015, for example, two containers shipped from Mombasa were seized in Singapore – they contained 178 pieces of ivory, four rhino horns and 22 teeth from big cats.

© MARTIN HARVEY / WWF

Worryingly, however, TRAFFIC estimates that wildlife products recovered in seizures represent just a fraction of the actual illegal trade. During the 2010–2016 period for which accurate rhino horn trade data exists, for example, seizures recovered 2,149 horns (either whole or in parts), but rangers recorded at least 6,668 rhinos poached. Assuming two horns are taken from each rhino, this leaves 11,187 horns unaccounted for.

Today the trafficking is run by ruthless international crime syndicates that are often also involved in other organised crime, including money laundering and the trafficking of drugs, firearms and people. They take advantage of increasing globalisation to elude their pursuers, constantly shifting smuggling routes and deploying ever more sophisticated tactics to conceal the goods.

In South Africa, rhino horn has been found smuggled inside toys, timber, fake electronic equipment and even bags of cashew nuts. A 2017 raid on premises in Germiston, near Johannesburg, uncovered a team processing rhino horn into discs, beads and powder.

Such syndicates also use money and power to exploit weaknesses at ports and borders, taking advantage of local corruption and weak law enforcement to traffic illegal products with virtual impunity. Seizures are no guarantee that traffickers will be caught.

“The problem is that usually the investigation never goes further than where the seizure occurs,” says Milliken. He despairs when shown the data, revealing, for example, that across south-east Asia in 2011, over 2 million live animals and around 8,000 dead animals, animal parts and derivatives were seized, yet only 231 arrests were made, and only 18 of these resulted in jail sentences and/or fines.

TARGETED

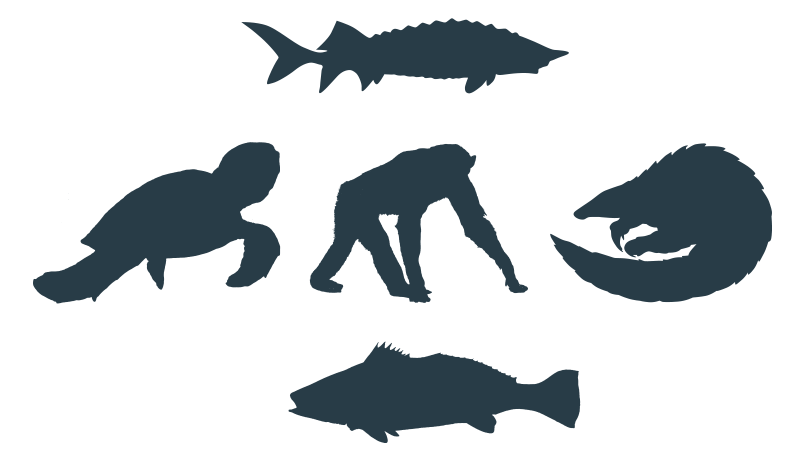

A huge variety of wildlife and wildlife parts is trafficked via land, sea and air from source countries to global consumer markets, where it’s used in various ways…

…ON THE MENU

Numerous wildlife species are targeted illegally for food. In China and south-east Asia, pangolin meat is a delicacy. Fish targeted include protected sharks, whose fins are used in soup. In Europe an appetite for caviar is putting sturgeon species at risk. In Africa, a thriving ‘bushmeat’ trade targets chimpanzees and other forest mammals.

Silky shark

One of the world’s more numerous sharks, this species has declined heavily – including by 90% in the central Pacific between 1950 and 1990. Like others, its fins are used to make an expensive soup for Asian markets. Research suggests this trade may claim more than 100 million sharks a year.

…HIGH STATUS

Economic growth in Asia is driving a new consumer market for wildlife products as status symbols. These range from elephant trinkets and rhino horn jewellery to mounted trophies such as gaur horns. Plants are also targeted: rosewood trees are illegally trafficked from Madagascar for luxury furniture.

Hawksbill turtle

Now critically endangered due to a rapid decline estimated at 80% over the past 100 years. Once the primary source of decorative ‘tortoiseshell’, this species – like other marine turtles – is also killed for its eggs, meat and skin.

African elephant

Around 17,000 African elephants are killed each year for their ivory. In four central African countries, forest elephant populations declined by 66% between 2008 and 2016.

…WANTED ALIVE

Slow lorises in Indonesia and fennec foxes in north Africa are among numerous ‘cute’ animals captured for the burgeoning wildlife pet trade. Other species in demand include parrots, crocodilians, geckos and tarantulas. Marine animals, such as the orange clownfish, are captured for aquariums, while orchids are trafficked to private collectors.

Tiger

The main sources of seized tiger parts are India and Thailand. Tigers from India are likely to be poached from the wild, whereas tigers from Thailand are likely to be taken from captive populations. All parts of a tiger are for sale – including paws, bones and penis – used both for medicine and as status symbols.

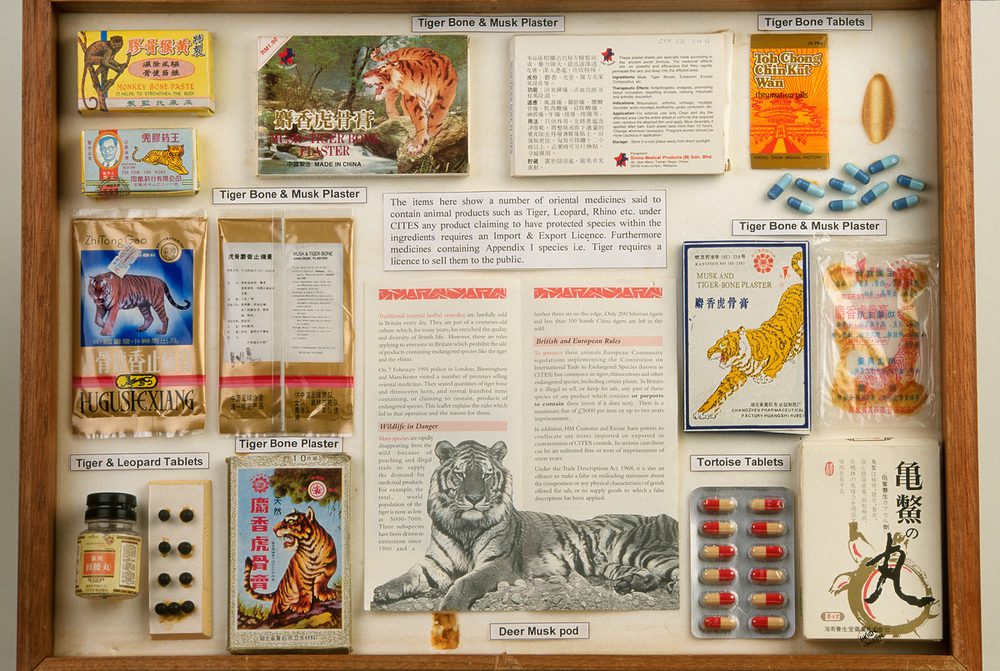

…KILL OR CURE

In Asian traditional medicine, folklore has long attributed healing properties to the body parts of wild animals. Tiger bones are used to treat rheumatism, pangolin scales for arthritis, elephant skin for skin problems and rhino horn for fever. Other species targeted range from musk deer to snakes and seahorses.

Black rhinoceros

The rarer of Africa’s two rhino species, with around 5,630 remaining. Now critically endangered due to demand for its horn – primarily in Vietnam, where it’s prized as a status symbol. In 2019, 594 rhinos (both black and white) were poached in South Africa.

Chinese pangolin

All of the world’s eight pangolin species are threatened. These insect-eaters are the most trafficked of all wild mammals, prized in China and Vietnam for their meat and scales (made of keratin, like fingernails), which are used in medicine and carved into ornaments.

BREAKING THE CHAIN

The illegal wildlife trade, like any trade, revolves around supply and demand. Reducing demand is undoubtedly the long-term solution – and we’re working with the governments of China and other key markets towards that end. But right now the situation is too critical to wait for demand reduction to bear fruit. “You can’t win this battle by just focusing on one side of the equation,” confirms Milliken.

Milliken explains how the immediate priority is to break the supply chain – and that to do this, effective law enforcement is the key. At present, the countries that are losing their wildlife, in particular in Africa, lack the resources to halt the trafficking. Milliken describes how prosecutions can founder on such simple obstacles as the lack of a Chinese language interpreter. “In case after case,” he says, “a whole body of intelligence is lost.”

Somebody needs to join everything up. “What we need is a Sherlock Holmes walking those trade chains and piecing it all together, then connecting different trade chains to various syndicates,” explains Milliken. “We need to ferret out these criminal syndicates and then get rid of them.”

For Milliken, breaking the trafficking chain depends on improving cooperation between the Asian countries where the markets are based and the African countries battling the problem on the ground. “I don’t think international collaboration on the law enforcement front is strong enough yet,” he worries. “I hope Asia can become a positive force in solving Africa’s problems. We need hands across the water: we’re in this together.”

© EDWARD PARKER / WWF

A WAY FORWARD

We’re determined to stamp out illegal wildlife trade by 2030. With your help, we believe it’s possible.

We’re continuing to focus our efforts on making sure leaders address the corruption that allows the illegal wildlife trade to escape the law, and also commit to giving rangers on the frontline proper equipment, training and insurance.

We want countries to make commitments to reducing demand for illegal wildlife products by changing consumer behaviour. We also aim to persuade other Asian countries to follow China, Hong Kong and Singapore’s lead and close their domestic ivory markets. Elsewhere, leaders in countries where poaching takes place must ensure community engagement is integral to tackling wildlife crime, as well as secure corridors that provide critical habitats for wildlife and benefits for people.

The good news is that we’ve already shown how, with your support, we can make an impact. Take Kenya: in three years, we helped the government to increase seizures of illegal wildlife parts, developed a forensics laboratory to provide prosecution evidence and, most recently, supported the training of special sniffer dogs at Mombasa port that can sniff out ivory, rhino horn and sandalwood in sealed containers. Similar sniffer dog programmes you’ve supported in India, Nepal and China exposed 23 major cases of wildlife crime in 2016 alone.

We’re also working on law enforcement – helping authorities to improve judicial systems and hand down stronger sentences to criminals. In Kenya, we were able to influence the government to pass landmark legislation to tackle wildlife crime: under the Wildlife Conservation and Management Act, which came into force in January 2014, people convicted now face fines of around £140,000 or life imprisonment, and in 2016 an ivory trade kingpin received a 20-year sentence.

© GETTY IMAGES

In the UK, we’ve helped gain political recognition and government funding for the National Wildlife Crime Unit, which provides expert support to stop illegal trade in threatened species here and internationally.

Meanwhile, we’re stepping up our work with CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), setting up national coordination committees in countries around the world to help ensure the convention’s agreements are respected and enforced. Putting pressure on governments to improve and enforce their regulations will help to end illegal wildlife trade once and for all, and we’re already seeing how governments can act.

We were delighted when the UK government committed to any ivory trade ban (it gained royal assent in 2018 but is yet to be implemented). And in 2017, China closed its legal domestic elephant ivory market, following a similar US initiative in 2016.

We can’t all be the wildlife trade Sherlock Holmes that Milliken calls for, but we can all play our part. Ultimately, wildlife trafficking will end if nobody buys the products. We each have a responsibility to make informed choices, and simple measures, such as only buying sustainably caught seafood, or wood products endorsed by the FSC (Forest Stewardship Council), make a difference. As Milliken points out, “We’ve got to know whether our decisions are going to make it a better or a worse world.”

• This is an edited version of an article that originally appeared in WWF Action magazine in 2018. Staff mentioned in this feature have since moved to other roles.

More to explore

Are tigers coming back from the brink?

For decades, we’ve worked tirelessly to secure a future for wild tigers. Now, as we approach a key milestone in tiger conservation, we need your help again