Many people won’t remember Ingleborough mountain as anything but a flat-topped landmark of the Yorkshire Dales – its second-highest peak, characterised by huge, broken slabs of limestone pavement.

At first glance, this is a bleak, almost barren, landscape where you might think you feel wildness in your bones. But the oldest farmers, who know the land, remember something different: a vibrant, colourful paradise.

Now, thanks to a visionary landscape-scale restoration project known as Wild Ingleborough, we’re hoping to return this iconic area to its former glory and create a better future for the UK’s uplands.

Reviving the wild

“The Yorkshire Dales is one of the UK’s most nature-deprived national parks,” says Lizzie Knight, WWF’s project manager for Wild Ingleborough. “It has the lowest amount of woodland cover of any of our national parks.”

Around Ingleborough, most of the woodland had been cleared long before the publication of the 1851 Ordnance Survey map. But what didn’t register on the map was the lattice of dwarf woodland that grew between the cracks in the limestone pavement. Nor did the map show the fields of wildflowers or the exuberant birdsong of spring.

At the start of the Second World War, farmers were still harvesting wood from the limestone pavement and raising cattle in these uplands. But increasing pressures on food production saw farmers respond to UK government demand, so cows were replaced with sheep – grazers that are more productive and easier to manage. The upland bogs, which had locked up vast amounts of carbon, were drained to grow more grass to feed the sheep.

In just a few decades, the sheep had bitten into Ingleborough’s natural assets, the heather eaten out of the upper reaches, and with it the iconic black grouse. The chorus of curlews, cuckoos and others grew much, much quieter.

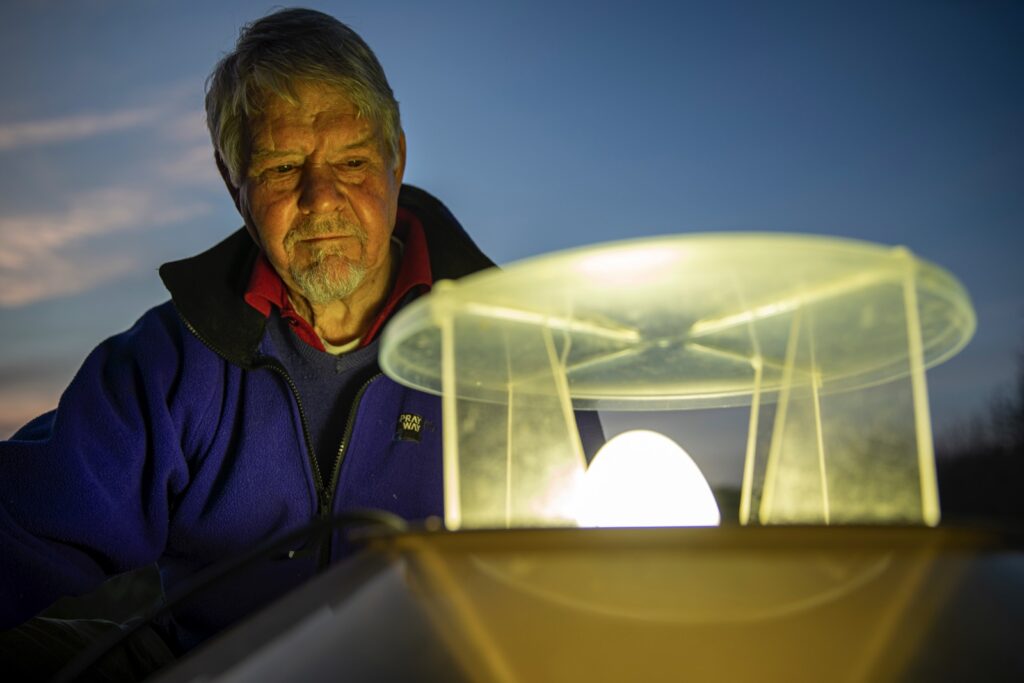

© JOSEPH GRAY / WWF-UK

Fortunately, there were still pockets of diverse habitat, primarily in nature reserves owned by Natural England and Yorkshire Wildlife Trust.

The Trust’s north regional manager, Jonathan Leadley, explains how the mountain’s remarkable geology gives the area a special botanical character: “The limestone bedrock produces a richness of grasses and flowers, such as early purple orchids, bird’s-eye primroses and cuckooflowers.”

Growing back better

Through the Wild Ingleborough project, we’ve partnered with these two organisations – as well as The Woodland Trust, the United Bank of Carbon, The University of Leeds and local communities – to help make Ingleborough a haven for nature and people.

An area of 1,200 hectares, from the River Ribble up towards Ingleborough’s summit, will see the re-establishment of the natural tree line, from broadleaf woodland to dwarf shrub, heather moorland and lichen heathlands.

The restoration of peatlands and the expansion of native woodland and scrub will store carbon and therefore help tackle the climate emergency. The project will also connect existing nature reserves in the area, creating a bigger area for wildlife to thrive.

“By making Wild Ingleborough a blueprint for restoration, we’ll demonstrate how UK nature can help fight climate change,” says Lizzie.

Six species at home in Wild Ingleborough

Curlew

They were once so common around Ingleborough that nobody bothered much about counting curlews, but changes in farming have drastically reduced their numbers. The parlous condition nationwide is reflected here, with only a handful of pairs nesting in recent years. Elsewhere, a shift towards growing grass for silage has meant that the birds don’t have enough time to raise a brood before the grass crop is harvested. By changing habitat management, we can encourage curlews to nest among longer vegetation on the mountain itself in years to come.

Juniper

Despite their appearance, the blue ‘berries’ of juniper are actually the fused scales of female seed cones. This short conifer, one of the rarest of our native trees, had all but disappeared from a large part of Ingleborough. Sheep nibbled down much of the growth and then a fungus-like tree disease – accidentally introduced into the UK – destroyed nearly three quarters of the remaining juniper forest. However, planting along the ghylls (mountain streams in narrow gullies) in unaffected areas allows the juniper to recover there.

Brown hare

Brown hares eke out a living in the Yorkshire Dales, surviving in one of the most exposed, challenging environments in England. Hardy as they are, they still need places to shelter during severe weather. Given time, the trees planted as part of the Wild Ingleborough project will provide just that. And hares much prefer feeding in areas grazed by cattle, since cows don’t nibble down the grass too much, so the switch of livestock from sheep to cattle will be a bonus. In winter, grasses will make up around 90% of a hare’s diet, though they’re able to feed on shrubs if the ground is covered in snow.

Black grouse

The decline in black grouse numbers probably began centuries ago when Ingleborough was stripped of much of its woodland. But they fell even more when the limestone pavement lost its trees and bushes after the Second World War. The black grouse is one of the UK’s fastest declining species. Today’s population on Ingleborough – largely reliant on the thin threads of woodland alongside streams – totals around 10 breeding males. As the new woodland grows, it will provide habitat for these special birds.

Bird’s-eye primrose

This gorgeous little mauve flower has the official name of bird’s-eye primrose, but in its northern England heartland it’s affectionately known as the Yorkshire primrose. A nationally scarce plant, it has become a jaw-dropping sight in May and June on the hillside at Sulber Nick, an area of Ingleborough where its flowers carpet the whole slope. These moisture-loving plants have blossomed since the meadow was grazed by cattle, not sheep.

Cuckoo

In spring, the most famous sound in nature echoes around the mountain. Cuckoos are widespread on Ingleborough. The female birds that fly here every summer most likely lay their eggs in the nests of meadow pipits, which are plentiful in the uplands. Cuckoos perch in cover on a high vantage point such as a tree or boulder, spying on the pipits to see where they land to nest on the ground. Wild Ingleborough is bound to benefit the cuckoos, as they rely on a supply of hairy caterpillars for food. More vegetation will mean more food.

Jonathan is helping lead the move to grow back better on the initial target area. Sheep numbers have come down and, in places, they have been replaced with cattle – less destructive grazers here.

“We must be agriculturally productive, but at the same time allow wildlife to flourish,” he explains, highlighting the project’s twin objectives to implement more sustainable farming.

Woodland that’s currently confined largely to streamsides is starting to spread to the slopes, thanks in part to thousands of trees donated by The Woodland Trust.

“We planted 30,000 trees in 2021 with the help of local volunteers and schoolchildren,” says Lizzie, “with potential for more.” The trees will cover an area roughly the size of 25 football pitches, and natural regeneration will create 25 more.

© JOSEPH GRAY / WWF-UK

This project is only possible with the wisdom and support of local people. We’re working with landowners, farmers and communities to share knowledge and skills to help overcome barriers created by more than 80 years of intensive grazing.

Heather and other upland plants that struggle to gain a roothold in thick, choking mats of grass will be given a leafy start in a new montane nursery. Blocking drains will make the blanket bog wet again, allowing peat to reform, moss to grow and carbon reserves to build. And tumbledown drystone walls will rise again to keep livestock in – or out of – sensitive areas.

When the children of the young volunteers who planted seedlings walk up the mountain decades from now, they will see a natural treeline from the valley towards the summit. They will ascend beside wooded streams, climb slopes clad in dwarf scrub, on through heather moorland echoing to the cries of black grouse, and over heaths of colourful lichens to the windy, exposed peak. And there they will stand, gazing at a world transformed below, and see what wildness is really all about.

The restoration of Ingleborough

Teams of experts and volunteers have been busy building, propagating, planting and monitoring across the Ingleborough landscape to help encourage it back to its former glory. (Best viewed in landscape orientation on mobile devices.)

© ANDREW PARKINSON / WWF-UK

Find out more

You can learn more about our work at Wild Ingleborough – and plan a trip to this unique landscape – on the Wild Ingleborough site.

More to explore

UK wildlife feeling the heat

The effects of climate change can already be seen close to home, with UK wildlife facing unprecedented challenges