“I’ve never seen such a vast expanse of agriculture before. It was like an ocean of crops as far as the eye could see,” recalls Tanya Steele, WWF-UK’s chief executive. “The skies were empty – there were no birds over the flat, monotonous landscape. I was shocked by the scale of it.”

It might sound like Tanya is recounting a visit to a farming region in the US wheat belt or midwest. But the scene of monoculture she surveyed during a visit in 2018 was in a deforested area of the Cerrado, a vast region covering 25% of Brazil’s land area. This habitat is often described as ‘savannah’, though it’s far more varied and, historically, rich with plant life than that suggests.

“Some parts of the Cerrado look like bush or scrubland, so the region’s importance can be underestimated,” explains Tanya. “Other areas are hugely forested. We call them ‘upside-down forests’ because of the depth of their root systems. There are plants here that are found nowhere else on Earth. They could be invaluable in ways we don’t yet understand – for nutrition or even medicine.”

© GETTY

It’s not just the Cerrado’s flora that makes the region special, though it hosts some 12,070 plant species. It’s also rich in animal life, with 837 types of birds, around 90,000 insects, 150 amphibians and nearly one in three of Brazil’s 700 mammal species, perhaps 40% of which are endemic.

It’s the source of water for eight of the country’s 12 river basins, and stores an estimated 13.7 billion tonnes of carbon. In short, this is a habitat Brazil – and the world – can ill afford to lose.

But it’s being cleared to grow the world’s crops – and at an alarming rate. Some 50% of the historical area of the Cerrado has gone already and an astonishing 18,962 sq km was lost between 2013 and 2015 alone – an area the size of Greater London every two months. In 2020 the Cerrado lost 7,300 sq km – 12.3% more than in 2019.

Tanya witnessed the problem first-hand. “We saw fires on the horizon, and evidence of recent deforestation and burning,” she reports. “They are huge fires, which generate so much smoke you can see them from miles away.”

Livelihoods up in smoke

Fires in Brazil hit international headlines in 2019 when, in August alone, more than 30,000 individual blazes were detected in the Amazon, nearly three times as many as in the same month the previous year. Less widely reported was that fires in Brazil’s Cerrado and Pantanal wetlands, as well as in Bolivia and Paraguay, also soared in 2019.

Manmade blazes are common in the Amazon during the dry season (August–October), as fire is used to prepare land for pastures and agriculture. But the scale and intensity of the fires in 2019 reflected sharp increases in forest clearance by ranchers, land grabbers, illegal miners and farmers.

This deforestation is largely unchecked by the Brazilian government. The total area burned in the Amazon from January to November 2019 was 70,647 sq km, 69% higher than the same period in 2018.

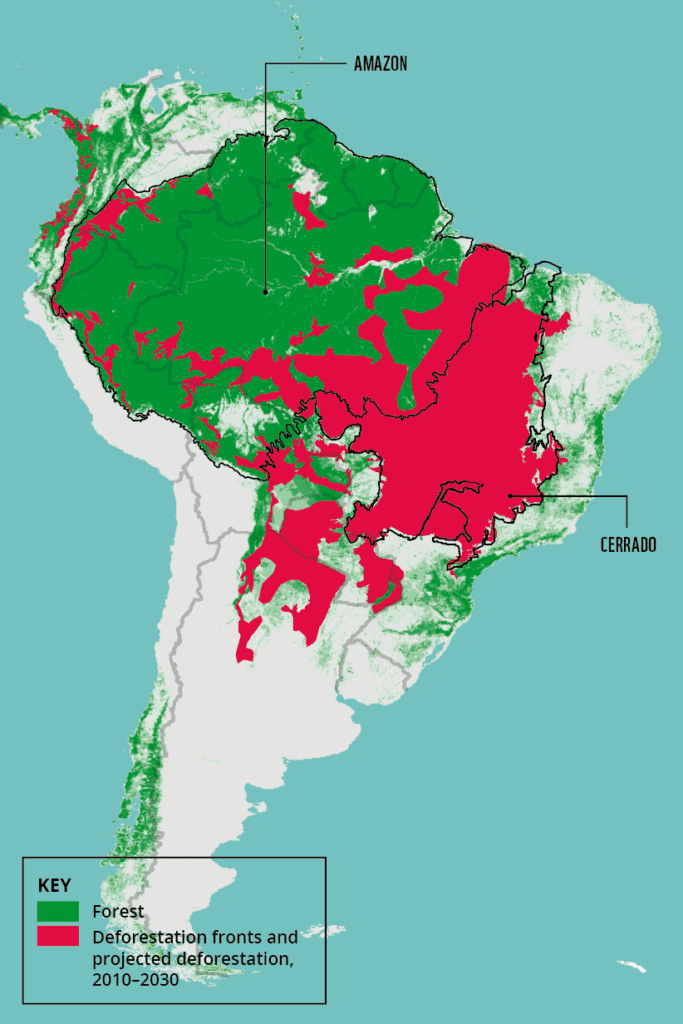

Though the Amazon is arguably the most visible example, it’s just one of 11 deforestation fronts worldwide identified by WWF. These are places where the largest concentrations of forest loss or severe degradation are likely to occur.

They include areas in the Congo basin and east Africa, south-east Asia, New Guinea and eastern Australia. Together, these account for over 80% of the forest loss projected globally by 2030 – up to 1.7 million sq km. We’re losing 88,000 sq km of natural forest worldwide each year – that’s an area the size of a football pitch every two seconds.

Forest frontlines

WWF’s Living Forests report identified 11 areas that are most vulnerable to deforestation between 2010 and 2030, including the Amazon and Cerrado.

Amazon

The world’s largest remaining tropical forest stores up to 140 billion tonnes of carbon. Over 17% of the Brazilian Amazon was cleared between 1970 and 2018, and a worst-case scenario could see over 25% of the Amazon’s remaining forests (854,000 sq km) lost by 2030. Primary drivers of deforestation are clearance for livestock farming, large- and small-scale agriculture, road and hydropower infrastructure development, extractives and logging.

Cerrado

Over half of the Cerrado’s natural vegetation has already been destroyed. In Brazil alone, between 2002 and 2010 almost 100,000 sq km was cleared, an area almost the size of Iceland. Official figures indicate that the Brazilian Cerrado lost 6,657 sq km of native vegetation between August 2017 and July 2018. Primary drivers of habitat loss are clearances for cattle ranching and soy plantations.

We know forests are globally important. They’re crucial for locking up huge amounts of carbon, and their loss contributes significantly to climate change – deforestation and forest degradation are the largest sources of CO2 emissions after the burning of fossil fuels.

Forests also moderate rainfall locally and regionally, and the loss or degradation of forests for food production, mining or other industries goes hand-in-hand with reduced water quality and increased flood risk, among other threats to the services nature provides.

The true price of cheap food

There are more personal impacts, too, as Tanya discovered in the Brazilian Cerrado. “We met families who had lived on the land for generations, but who have now lost their rights to it,” she reports.

“As global demand for soy production has increased, land-grabbing has become a real problem here. Mariene Gomes Lopes, her brother and her 84-year-old parents were displaced from their ancestral home in the Cerrado to make way for food production. Suddenly, they had no choice but to travel to the city to find work and build a new home.”

These stories may reflect problems on different scales – vast tracts of forest burned to clear land, contributing to increasing greenhouse gas emissions, versus individual families being displaced – but one troubling aspect links them: as consumers we are unwittingly complicit through our food choices.

What we eat has a huge impact on nature in far-flung places, particularly as global diets change to include more meat, dairy and processed foods. The UK food supply alone has been directly linked to the extinction of an estimated 33 species at home and abroad. As Mariene’s mother told Tanya: “There’s no such thing as cheap food – it has a cost thousands of miles away.”

Large-scale forest clearance in Malaysia and Indonesia has been driven by demand for palm oil, used in nearly 50% of packaged products found in UK supermarkets.

And in west African countries such as Ivory Coast, which supplies 30% of the cocoa beans for the world’s chocolate market, tropical forests are typically cleared to plant new cocoa trees rather than reusing the same land. It’s been estimated that 70% of the country’s illegal deforestation is related to cocoa farming.

© DAVID BEBBER / WWF-UK

In Latin America, one of the biggest problems linked to a global increase in meat and dairy consumption is clearance of natural habitats for cattle pasture in areas such as the Amazon. And, in the Cerrado particularly, there’s a further issue – soya bean agriculture. The UK consumes some 3.3 million tonnes of soy each year, over 75% of it ‘hidden’ in the animal products we eat, such as meat, dairy and eggs.

Right now, we have no way of knowing where the deforestation is found. It’s buried deep in our food supply chain. For example, soy can be grown on deforested land abroad and then fed to British-grown chickens and pigs.

Soy can be grown sustainably, but 77% of UK soy imports currently come from Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay – countries where there’s a high risk of deforestation, weak governance and poor labour standards. And our food supply chain rarely distinguishes between sustainable soy and that which drives deforestation.

People power

The tragedy, but also the opportunity, is that it doesn’t have to be this way. “The real crime is that there’s no need for even one more tree to be chopped down. Existing cleared land can still be farmed productively,” says Tanya, referring to soy farming in the Cerrado. “We already have more than enough land to feed the world’s growing population and we don’t need to destroy any more precious habitats.

“But the nature of the incentives for some farmers, and the way in which they’re managing stewardship of that land, means that it’s cheaper for them to deforest the next stretch of trees than to look after the soil and the land they already have. So we’re looking at how we can work with those agricultural producers – many of whom want to change – to take better care of the land that’s already cleared.”

In practical terms, that means changing the way soy is farmed: being more mindful about the use of the land, leaving buffer zones in place for wildlife corridors between some of the large-scale agricultural areas, and not farming right up to the edges of rivers, to provide space for wildlife and reduce chemical run-off that could enter rivers and poison fish.

We’re also working with local cooperatives harvesting non-timber products such as pequi, baru nut, cashew and babassu coconut, helping them to make a living and encouraging conservation of those trees. There’s no time to lose: if the destruction of Cerrado habitat continues at recent rates, 150,000 sq km could be lost by 2030, and some 480 of its plant and animal species could become extinct by 2050.

Working with local farmers is just one part of the puzzle; we need to ensure it’s viable for them to improve their farming practices. “Many farmers feel a huge pride in and connection to their land. They’re already looking at ways to manage their crops in a more sustainable way,” observes Tanya.

“One of the things we’ve been asking retailers, big businesses and agricultural suppliers is to create a level playing field – a fair system so farmers can do the very best for their own land and investment.”

The loss of forests threatens…

The world’s climate

Deforestation and forest degradation contribute significantly to global emissions of carbon dioxide, the most prevalent of the greenhouse gases linked to climate change. Over 40% of the carbon stored in the world’s forests is found in three places: the Amazon, the Congo and south-east Asia.

Local livelihoods

Forests provide food, shelter, fuel and income for about a billion people around the world. Forest products on which local people depend are threatened by deforestation – for example, baru nuts, babassu coconuts and pequi fruit and nuts are used by communities including indigenous and quilombola settlements (founded by escaped Afro-Brazilian slaves) in the Brazilian Cerrado.

Biodiversity

Forests are home to well over half of the world’s land-based species. Recognised as a global biodiversity hotspot, Brazil’s Cerrado has an abundance of species, many of which are found nowhere else on Earth. They include 12,070 native plant, 252 mammal, and over 800 fish and bird species.

Water

Deforestation affects water cycles and quality. Trees absorb groundwater and release it into the atmosphere in a process called transpiration; deforestation impacts the climate locally and further afield, making it drier, and also affects the water table. The removal of trees near waterways leads to more soil eroding into rivers, increasing sedimentation. Along with pollution from agriculture or mining, this causes changes in water quality and flows.

Importantly, the choices we make in the UK have an impact right along the supply chain. So we’re pushing the UK government to develop policy frameworks to ban the sale of any food that causes deforestation. We called on the government to ensure businesses are legally required to address deforestation in their supply chains. As a result it amended the Environment Act to make it illegal for companies to import commodities causing deforestation.

This is a great first step but doesn’t go far enough, as it only addresses legal deforestation as defined by the law in the country of origin, which carries the risk of weakening environmental legislation and still permitting legal deforestation. WWF is therefore continuing to push to strengthen the due diligence requirements.

Tackling our footprint

We’re also asking businesses to do their fair share to make our supermarket shelves deforestation- and conversion-free (in order to preserve not just forests, but savannahs, grasslands and other habitats). In November 2021, UK industry leaders from 27 major businesses signed the UK Soy Manifesto, committing to buy only soya that has been grown without deforestation or the removal of native vegetation as soon as possible, and by 2025 at the latest. They include Tesco, Nestlé, Sainsbury’s, Nando’s, KFC UK and Ireland, Morrisons, and McDonald’s UK and Ireland.

There are other ways we can help reduce our impact, too. “Think about where your food comes from, and how it’s been produced. Ask your local supermarket, butcher or grocer about the source of the food you’re buying,” says Tanya.

“It’s not about turning your life upside down. But there’s no doubt we have to change our diet and our food choices for the future – to ensure the environment is in good health for our children. By making some changes to our diets we can be a bit healthier, too. It’s a positive thing for us all.”

© GETTY

What does this mean on a day-to-day level? Well, it’s true that meat – particularly beef and lamb, and to a lesser extent pork, fish and chicken – has a large environmental footprint, so eating less meat is helpful. But reducing our impact is about eating better, rather than just less.

For example, beef cattle raised on deforested land is responsible for 12 times more greenhouse gas emissions than cows reared on natural pastures. And palm oil can benefit communities and wildlife when it’s sourced sustainably.

It’s not always easy to know the provenance of our food, but there are tools to help. Look for RSPO (Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil) certification on products, or check the WWF Palm Oil Scorecard to see how retailers, restaurant chains and food manufacturers are performing in terms of sustainable sourcing.

And the nifty Giki app allows you to scan the barcodes of some 280,000 popular products to obtain information about their environmental and ethical credentials.

Local and global solutions

We know we must act quickly to halt deforestation. There are enormous challenges – local and global, economic and political – particularly in places such as Brazil, where the current administration has demonstrated a lack of will to tackle climate change, deforestation and loss of biodiversity.

But with your help, we can continue to collaborate with governments, local communities and Indigenous groups in other key countries such as Colombia, Peru and Bolivia to combat deforestation in Latin America and elsewhere. And by considering what you eat, and making choices based on the effects of those products, you can have a huge positive impact on nature.

We’re realistic about what’s required, but also optimistic about what can be achieved. “We need to feed a growing population, and we have to do that as effectively and efficiently as possible,” affirms Tanya.

“This is a story not only about deforestation or damaging one of the most important biodiverse places on this planet. But it’s also about our food choices and food system, and how many of the products we eat have an impact thousands of miles away. Finally, it’s about changing the balance of nature and effectively addressing climate change for future generations.”

Fight for forests

Take a look at our ‘promises tracker’ to see the progress the UK government has made so far on its commitments to tackle the UK’s global environmental footprint and protect vital forests like the Amazon.

• This is an edited version of an article that originally appeared in WWF Action magazine in 2020.

More to explore

A burning problem

Around the world, wildfires are raging with unprecedented ferocity. But with your help, we’re taking action to tackle the causes and help communities deal with these devastating blazes