A soft alto voice swells in the darkness. Rising to a strident treble, it swoops and soars, then settles into a soothing adagio, ebbing and flowing in pitch, volume and urgency. Eventually the last note recedes, and another mesmerising performance by the Arctic’s oldest crooner is over.

The bowhead whale – the longest-lived mammal on Earth, reaching 200 years old – has been dubbed ‘the jazz singer of the Arctic’, intoning diverse melodies almost non-stop during its winter mating season.

In truth, the bowhead is more Miles Davis than Al Jolson, its music akin to that maestro’s free-jazz horn playing – and just as varied. A three-year study published in 2018 recorded 184 different song types in just one area, the Fram Strait between Greenland and Svalbard.

The bowhead’s unique vocalisations are accompanied in the Arctic by a range of other sounds: whistles and clicks of narwhals and belugas, creaking of ice, barks and grunts of seals and walruses.

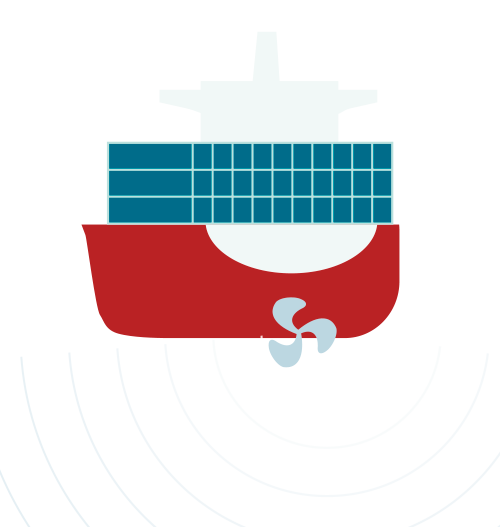

But they’re being increasingly backed by an expanding and disruptive percussion section – the rhythmic throb of ships’ engines, the airgun shots of seismic surveys, the thump of piledrivers. In short, the sounds of humans accessing areas that were previously icebound and therefore inaccessible.

© ALAMY

The 2019 Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) makes sobering reading. It concludes that the current loss of summer Arctic sea ice is at its worst in at least 1,000 years. IPCC models project continued declines in Arctic sea ice through to the end of the century.

The loss of sea ice opens up areas of the Arctic that were historically inaccessible to human activity, presenting economic opportunities – for exploitation of mineral resources, for shipping navigation, for installing infrastructure such as wind turbines, and for ship-based tourism – but also potentially detrimental impacts.

Along with oil spills and ship strikes on marine wildlife, there’s another, less well-studied threat: underwater noise.

Shrinking sea ice

We know that maritime traffic in the Arctic has grown. The IPCC suggests that shipping activity during the Arctic summer increased significantly over the past two decades, concurrent with reductions in Arctic sea ice.

The Northern Sea Route along the Arctic coast of Russia can cut the distance between ports in east Asia and Europe by 30–40% compared with using the Suez Canal, and traffic on that route increased significantly from 2009 (two vessels) to 2013 (71 vessels).

Similarly, the Northwest Passage speeds up travel between north Atlantic and north Pacific ports. Because more vessels are taking advantage of this shorter route, the total distance travelled by ships in Arctic Canada nearly tripled between 1990 and 2015.

As shipping traffic grows, so does noise – an effect more noticeable in the formerly tranquil Arctic Ocean.

The sound of marine animals

Bowhead whales

Bowhead whales sing for almost 24 hours a day in winter to woo mates.

Narwhals

East Greenland narwhals spend on average 27% of their time echolocating.

Beluga whales

Noise can damage beluga whales’ hearing by causing a loss of hair cells in their ears.

Walruses

Underwater noise makes it hard for walrus mothers and calves to find each other if they’re separated.

“Noise travels at a shallower depth in Arctic waters,” explains Dr Melanie Lancaster, WWF’s Arctic species specialist. “Also, ice blankets the water from wave and wind action for much of the year, so it’s much quieter than most of the rest of the world’s oceans. Hence we think that the marine wildlife of the Arctic is less used to noise than animals in other regions.”

Shipping is not the only human activity that produces noise. Vessels exploring for oil and gas reserves use seismic airguns to survey the seabed, and construction of infrastructure such as wind turbines often involves percussive piledriving, both increasingly common in the Arctic as summer sea ice becomes less extensive.

Increasingly, then, manmade noise may mask or obscure important natural sounds, heighten stress levels among animals and change their behaviour.

The search for harmony

Narwhals and belugas, both Arctic residents, produce a range of vocalisations – squeaks, whistles and clicks – for communication and echolocation. Research in the western Canadian Arctic showed that recorded beluga vocalisations decreased significantly when vessels were close, suggesting that belugas either moved away or reduced how often they vocalised in response to traffic.

Another study in the Canadian high Arctic found that belugas showed a strong ‘flee’ response to an icebreaker between 35km and 50km away. “Imagine yourself in a noisy restaurant where you have to keep raising your voice to be heard,” says Melanie, providing a helpful analogy. “You have a couple of alternatives: you don’t talk as much, or you just go somewhere else – and belugas seem to do one of these things.”

It’s a similar story for our sub-aqua soloists, bowhead whales. An acoustic study in the Alaskan Beaufort Sea found that their communication rate dropped significantly near airguns during seismic surveys. This may be because the whales stopped calling, moved away, or both. It’s also noteworthy that bowhead courtship songs are a similar frequency to ship noise, so they are more likely to be masked.

The rise of shipping noise

- 90% of all goods travel by ship.

- The distance travelled by ships in the Canadian Arctic has nearly tripled in 25 years.

- In 2017, almost 90 vessels travelling the Northern Sea Route violated safety rules.

- 60,000 commercial tankers and container ships are on the seas at any given time.

- Recorded underwater noise from ship traffic is doubling every decade.

- Arctic shipping traffic is expected to quadruple by 2025.

Arctic cod, too, react to vessel noise by moving away from the sound and curtailing their exploratory activities, which reduces the distance over which they forage, so they’re less effective at finding food. Indeed, manmade noise is the biggest factor affecting the ability of fish in various marine environments to feed, avoid predators and reproduce successfully.

Older studies suggest that narwhals ‘freeze’ at the approach of ships, staying still and silent. But more research is needed. We’re working with the Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans on a long-term seasonal project at Tremblay Sound, Baffinland.

This is an important summer area for narwhals that’s also close to an iron-ore mine opened in 2014, which drives ship traffic through the Sound via the Arctic Bridge Route. By satellite-tagging narwhals, we hope to improve our understanding of this cetacean’s ecology and the impacts of climate change – including increased noise from shipping.

Changing behaviour

We also need to understand larger-scale impacts. “Ship noise doesn’t necessarily cause injury or death, but it does tend to change the way animals behave,” Melanie explains. “It might cause animals to temporarily move out of an area where they’ve been feeding, for instance, and the result could be mass displacement of animals, separating large numbers from their food source. It’s important for us to understand how those behavioural changes will have an impact at population level.”

Clearly, further research is crucial. We need to record underwater noise levels now so we can measure future increases. We need to further study the ecology of Arctic species, and how they react to increased underwater noise. And we must work to limit these impacts.

“Currently, we’re working with the government of Canada and the Arctic Council working group on the Protection of the Marine Environment to map underwater noise from shipping across the Arctic, and overlay this with important areas for Arctic biodiversity,” reports Melanie.

“We’re aiming to understand what the normal background levels are, to identify quiet areas that could potentially be sanctuaries for marine mammals and other wildlife, and to define areas that are already starting to get noisy.”

© PAUL NICKLEN / NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC STOCK / WWF-CANADA

On a global scale, we’re following the upcoming submission by the governments of Canada, Australia and the US to the Marine Environment Protection Committee of the UN International Maritime Organisation (IMO, the global shipping regulator) to put underwater noise back on its agenda.

By highlighting the global nature of the problem, we’re hopeful that many of IMO’s 174 member states will recognise the need for new action on this issue.

The UK doesn’t have Arctic territory, but it has £279 billion invested in companies that are active in the region. We’re working to influence the UK government’s Arctic Policy Framework to ensure activity in the Arctic is sustainable. This includes following our Arctic Blue Economy principles and steering away from oil and gas extraction that accelerates global warming and the loss of sea ice. And we’re continuing our efforts to ensure the UK government follows through on its commitment to meet a net-zero emissions target.

There’s much to be done to understand and manage the impacts of underwater noise in this beautiful region. But with your help, we hope to ensure that the love songs of bowheads will continue to serenade the Arctic for many centuries to come.

The effects of oil and gas

- Oil and gas exploration uses seismic airguns that are six to seven orders of magnitude louder than the loudest ship sounds.

- The sounds they emit are a similar frequency to cetaceans’ communication signals, causing confusion among marine mammals and increasing the potential for harm.

- Ships with airguns fire them every 10–12 seconds for weeks or months. The sound can travel further than 4,000km.

- According to a 2014 report, Inuit people throughout the Arctic say seismic surveys are driving animals away from their hunting grounds.

• This is an edited version of an article that originally appeared in WWF Action magazine in 2020.