It’s April in Ittoqqortoormiit, an Inuit settlement of about 450 people on the east coast of Greenland. There’s a haunting, raw beauty to this isolated spot, with its backdrop of basalt cliffs soaring from the edge of Kangertittivaq (Scoresby Sound), reputedly the world’s largest fjord system.

But, lying several degrees above the Arctic Circle, even in early spring the mercury only just nudges over -10°C. It’s a day to wrap up warm and travel quickly.

A man steps from one of the colourful cabins studding the rocky shore and jumps on his snowmobile, ready to head along the coast as he does most days. Suddenly, a polar bear appears and, taken by surprise, charges straight at him.

The animal is quick – polar bears can sprint as fast as Usain Bolt – and with little time to react, the man defends himself the only way he can: with his bare hands, boxing the huge predator in the head.

The bear is young – a full-grown adult male can be as much as 2.5m long and weigh 680kg – but it’s still many times bigger than the man. Finally, after fending off the bear with his blows, the man manages to start his snowmobile and escape. Hands swollen from desperate punching, jacket wet with the bear’s saliva, he’s shaken but safe.

© NATUREPL.COM / STEVEN KAZLOWSKI / WWF

It’s an incredible story, but one WWF’s Kaare Winther Hansen knows is all too real. This incident was the closest polar bear encounter in the region for seven or eight years, but it’s far from the only one.

Incidents are rising at an alarming rate. In 2007, nine polar bear conflicts were registered in Greenland. Between August and December 2017, there were 21 close calls with bears in Ittoqqortoormiit alone. This pattern is repeated across the species’ range in Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Norway and Russia.

The primary cause is climate change, which has had a disproportionate impact on the Arctic: since the 1980s, this region has been warming at almost three times the global rate. Though polar bears are strong swimmers (the scientific name, Ursus maritimus, means ‘sea bear’), they depend on sea ice to hunt – mostly ringed and bearded seals – and to travel to their winter denning sites.

As climate change bites, sea ice melts earlier in the year and freezes later, and its extent and thickness is reduced; scientific models predict that most of the Arctic will be largely free of sea ice during the summer months by 2040.

© NATUREPL.COM / SERGEY GORSHKOV / WWF

Easy pickings

The effects of sea ice reduction on polar bear movements are felt acutely in communities such as Ittoqqortoormiit. “Polar bears follow the edge of the sea ice as it retreats north in spring,” says Kaare. “In the past five or six years, the edge has been much closer to the shore, so the bears can smell the settlement – particularly dog food and the dump site.”

The chance to scavenge easy pickings is tempting, particularly to hungry young bears (typically around three years old) that recently left their mothers and have yet to hone hunting skills – “angry teenagers”, as one local calls them.

Even in Greenland, where communities have lived alongside polar bears for centuries, this increase in incursions by huge predators is alarming. “We worry more these days. We’re always on the lookout for bears, from the early morning to late at night,” explains an Ittoqqortoormiit resident. “We dare not send our children out on their own.”

There have been no reported human deaths or serious injuries from polar bear attacks in Greenland in the past century, but the risks to people and property are growing. “When I was a kid, we never saw polar bears in this area,” says one 64-year-old resident. “Now we have to polar bear-proof our cabins. Last spring, a bear smashed all our windows.”

One drastic solution to ‘problem’ bears is to shoot them, which is legal when in defence of life or property. But given the pressures that polar bears are already facing, having a number of non-lethal options in the conflict toolbox is a must.

Though accurate figures across the Arctic are wanting, the Polar Bear Specialist Group of the IUCN estimates a global population of 22,000-31,000, and predicts that this could decline by more than 30% by 2050.

Thanks to your support, we’ve worked with governments and Arctic communities for over a decade to mitigate the risks to both bears and people. One effective measure you helped us to introduce is polar bear patrols.

The first of these was established in 2006 in Chukotka, north-east Russia, where umky (polar bear) patrols use long sticks and other means to drive away problem animals, averting fatal interventions. Today, WWF supports patrols across four countries: Alaska, Canada, Greenland and Russia.

© ANTHONY DICKENSON / ALL MIGHTY PICTURES / WWF-UK

Ittoqqortoormiit’s community-led patrol was established in 2015, largely in response to concerns about the safety of schoolchildren in the face of increasing bear incursions. Thanks to our members and polar bear adopters, we provided an all-terrain vehicle (ATV) – essentially a hardy quadbike – and we fund a patrol each weekday morning before school, during periods of peak bear activity. Typically, the patrol is needed from August, though in 2018, because more bears were sighted in earlier months, we also ran a patrol in spring. And it’s been busy: “In the first three seasons of patrols, I recorded 65 polar bear incidents,” reports Kaare.

When the patrol encounters a polar bear near a community, it tries first to drive it away. “The most effective deterrent is the ATV itself – the noise of the engine is usually enough to scare off bears,” says Kaare. “If this doesn’t work, the noise from a powerful rifle is often effective. We’re also testing a loud signal gun.”

Tactics and challenges

Running the patrol isn’t without challenges, not least keeping the ATV running in such extreme conditions. Only two ships visit Ittoqqortoormiit each year, so sourcing spare parts can take time. And spotting polar bears isn’t always straightforward, as one patroller reports: “The landscape is vast and plays tricks on the eyes: sometimes a stone or a patch of snow resembles a polar bear; sometimes things seem closer than they are.”

With your support, we’re also working to make the settlement less attractive to bears. Though dog food (mostly walrus and seal meat stored outside in wooden boxes) and areas where hunters process their catches can attract bears, the main ursine fast-food joint is the town dump.

“Even fresh polar winds can’t remove the stench,” observes one local. “Polar bears follow the smell of rotting meat – it’s a feast for a starving bear.” The town has an incinerator, but it’s ineffective, so Kaare has been working with the municipal government in Greenland’s capital, Nuuk, to introduce a system for packaging and shipping out bear-enticing waste.

Such combinations of tactics have proved effective elsewhere. In 2010, you helped us to introduce polar bear patrols and bear-resistant steel food-storage bins to the Inuit community of Arviat in Nunavut, Canada. As a result, on average seven fewer bears are shot each year in defence of life and property.

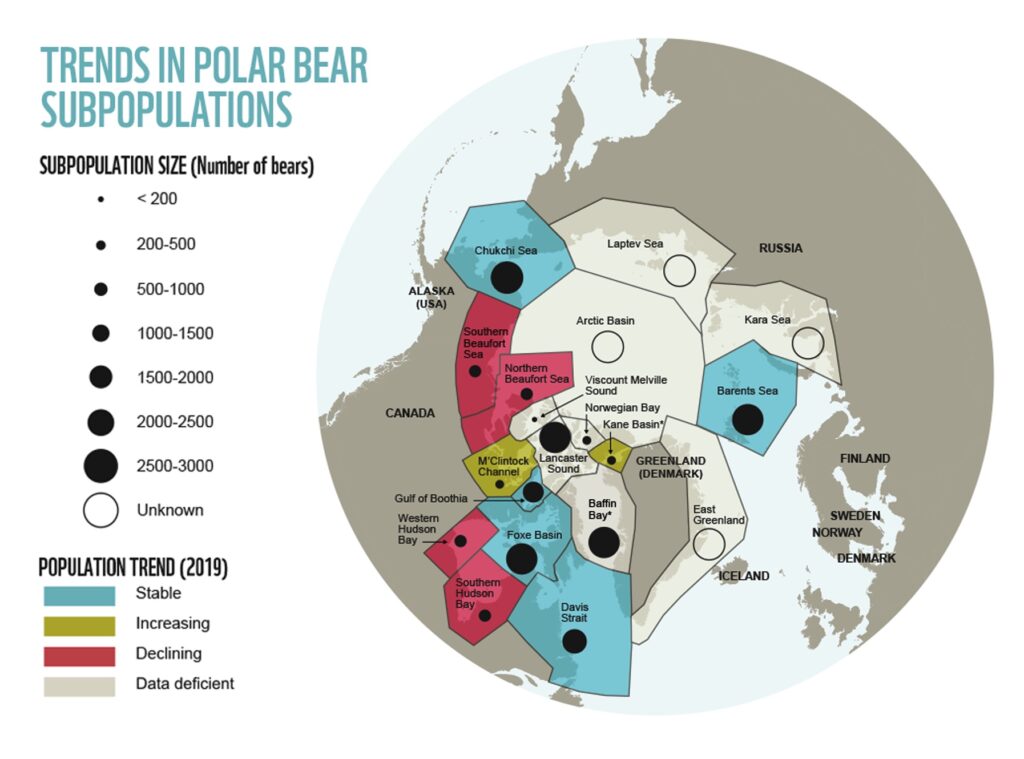

GRAPHIC PRODUCED BY WWF CANADA, JUNE 2017. UPDATED OCTOBER 2019

Polar bear alerts

We’re also exploring new technology that could help us to tackle the problem. In 2017, we ran a competition with our partners, the conservation tech network Wildlabs.net, to find solutions to conflict between people and wildlife. One of the winning entries, by the UK-based Arribada Initiative, combines infrared and thermic sensors to create a cost-effective, easy-to-use thermopile infrared system that could detect and identify different species (automatically distinguishing between dogs and bears, say) and send alerts to a patroller’s mobile phone.

Of course, local incidents reveal just part of a much bigger picture. To help understand and manage human-polar bear conflicts, we encourage the logging of encounters in the Polar Bear-Human Information Management System, a database to record and better understand conflict between people and polar bears around the Arctic. But our overall understanding of polar bear ecology is still inadequate.

The estimate of the total population is woolly, and nine of the world’s 19 subpopulations are classed as ‘data deficient’, including those of east Greenland (though an ongoing government survey should provide figures by 2022). Obtaining accurate information about bear populations, movements, diet and other details is crucial – and tech advances will again play a key role.

In Nunavut, we joined a team biopsy-darting bears to obtain tiny samples of hair, skin and fat, providing genetic ‘fingerprints’ for individual bears as well as information on their diet and general health. In Alaska and in Svalbard, Norway, we’re working with partners to get these same genetic ‘fingerprints’ from polar bear pawprints left in the snow. We hope that, with refinements and the involvement of local communities, this will contribute towards polar bear population data across the Arctic.

We’ve contributed to the deployment of thermal imaging for an aerial census of polar bears and ringed and bearded seals in the Chukchi Sea to help survey vast areas quickly and accurately. And we’re working with scientists, technicians, engineers and native peoples in Alaska to develop new tracking technology, which could replace unwieldy collars that haven’t evolved much since the 1980s.

There’s much more to be done. In 2013, the five nations that are home to polar bears renewed their joint commitment to polar bear conservation, developing the Circumpolar Action Plan (CAP), a 10-year strategy with 62 actions. Yet two years in, WWF’s scorecard found that only three of those actions had been completed.

That said, there is cause for optimism, not least in the sense of connection and responsibility in local communities. As one young hunter in Ittoqqortoormiit said: “If polar bears were gone from the Earth, we would have failed nature, ourselves and future generations. I cannot imagine living in a world without polar bears, and would feel great guilt if I had behaved in a way that instigated or escalated this situation.”

There are clearly some huge threats and challenges ahead for Arctic people and wildlife. But there are also great opportunities – if we can seize them now. With your support, we can chart a brighter future for this spectacular region and its magnificent polar bears.

© ANTHONY DICKENSON / ALL MIGHTY PICTURES / WWF-UK

Help protect these icons of the ice

Your membership is already helping people live alongside polar bears. But if you’d like to do more, here’s how…

Adopt a polar bear to help us tackle conflicts and mitigate the impact of climate change

Learn how you’re helping to protect the Arctic and its wildlife

Find out how to reduce your environmental impact

• This is an edited version of an article that originally appeared in WWF Action magazine in 2018.

More to explore

Thermal tech in the Arctic

We’ve tested cutting-edge technology using thermal cameras to help polar bears and people live together more safely