The emperor penguin lives life on the edge. The largest of the world’s 18 penguin species inhabits the very margins of Antarctica, where the frozen boundary dividing land from icy sea shifts between the long, dark winter and all-too-brief summer.

It’s an already extreme existence that looks more challenging in the face of global climate change. So we’re tapping into satellite technology to increase our knowledge about this majestic bird and inform conservation efforts to give it the best chance of surviving into the 22nd century.

Here’s what we do know about the emperor penguin. Reaching up to 120cm tall and 40kg in weight, this flightless, semi-aquatic species has evolved several characteristics that enable it to endure the bitter Antarctic cold.

Insulated with ample fat reserves and two dense layers of feathers, it has small flippers, feathered legs and clawed feet that contain special fats. Along with regulating blood flow, these fats prevent the penguin’s feet from freezing when temperatures plummet as low as -50°C.

It can dive deeper than 500m to hunt silverfish, squid and krill, staying underwater for over 20 minutes. With its smart black tux, white chest and yellow collar, it’s strikingly dapper.

© FRITZ PÖLKING / WWF

Emperor penguins are the only penguins that breed during the Antarctic winter. They don’t build nests, but instead balance their single egg on their feet. Each female produces one egg between May to June, early in the austral winter, so that her chick will be developed enough to venture to the sea in December to January, where they will stay the rest of the summer, feeding independently.

The entire breeding and rearing process takes place in huge colonies, or rookeries. These can comprise thousands of birds on fast ice – sea ice that covers the ocean but is firmly attached to land.

Balancing act

“Emperor penguins are the only birds that breed on sea ice,” explains Rod Downie, our chief adviser for the polar regions. “For about nine months of the year they rely on the stable platform provided by fast ice: they mate on it, incubate their eggs on it, raise their chicks on it, and moult on it.”

‘Goldilocks’ sea ice conditions are, therefore, essential for breeding success: not too little, but also not too much – extensive unbroken sea ice forces adults to travel further and expend more energy accessing open water to hunt while incubating and rearing chicks. And conditions look set to deteriorate.

“Most predictions anticipate a significant loss in Antarctic sea ice caused by global climate change,” says Rod. “Some models suggest that, if global greenhouse gas emissions aren’t curbed now, over 80% of emperor penguin populations could be lost by 2060 and the species will be virtually extinct by the end of the century. There’s a clear link between climate change and emperor penguin populations.”

Already we’ve seen one of the world’s largest emperor penguin colonies at Halley Bay almost disappear after three consecutive years of breeding failure, largely because sea ice broke up earlier than usual.

How satellites survey polar species

Penguins

Scientists use aerial and satellite images to locate penguin colonies and spot population trends for chinstraps, Adélies and gentoos. Some breeding sites are identified from the colour of the penguins’ poo.

Whales

British Antarctic Survey (BAS) has pioneered the use of very high-resolution (VHR) satellite imagery for identifying and counting species including humpback, sei, fin, grey, blue and southern right whales.

Seals

VHR satellite images are used to study Weddell and crabeater seals. New methods combining these images with artificial intelligence, thermal imaging and spectral analysis will help to detect and count seals.

Albatrosses

Surveying the breeding sites of great albatross species – all threatened with extinction – on remote islands is difficult, so BAS has developed systems for counting the birds using VHR satellite imagery.

Walruses

Join the five-year Walrus from Space project to conduct a census of Atlantic and Laptev walrus populations using satellite imagery, and help scientists better understand the impacts of climate change. Sign up at wwf.org.uk/walrus-from-space

One challenge conservationists faced until recently is that we knew relatively little about emperor penguin populations, colony locations and feeding areas. This is a consequence of the challenges of researching in such an extreme environment, where remote sites are difficult and expensive to reach and monitor.

Satellite technology plays an important role in this. For example, we’re working with British Antarctic Survey (BAS), using satellite imagery to fill in gaps in our knowledge about the location, size and trends in emperor penguin colonies.

Satellite tagging of various bird species reveals migratory movements and locations of breeding, feeding and wintering grounds. Recording such data enables scientists and conservationists to identify changes in behaviour and locations.

In addition, satellite images of the Earth’s surface reveal significant habitat and land-use changes – notably, in light of the climate emergency, reductions in forest cover and seasonal extents of land and sea ice. Increasingly, high-quality satellite imagery is being used to survey wildlife populations, too, identifying groups and, in some cases, even individual animals.

penguin prospects

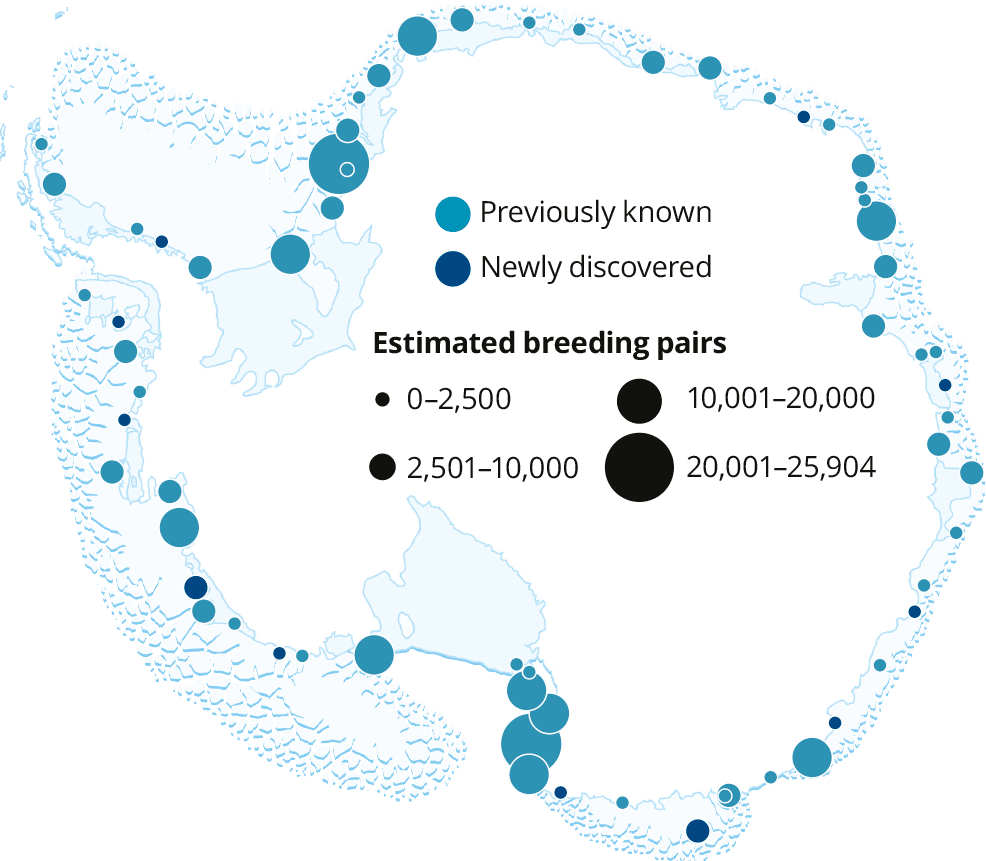

This map shows the location of all known emperor penguin colonies in Antarctica, and the estimated number of breeding pairs, including the newly discovered colonies.

(Note that of the 65 breeding locations only 61 are currently occupied)

“Satellite technology has advanced tremendously in recent years,” says Rod. “We now have access to commercial satellite imagery that’s highly detailed. We can identify the locations of emperor penguin colonies from the stains produced by their guano, which are visible on the satellite images – the clue’s in the poo!”

WWF has worked with BAS for a number of years on projects using satellite imagery to detect and monitor emperor penguin colonies, comparing their sizes with estimates in previous years.

In 2020 BAS reported the results of a multi-year satellite imagery study that identified 11 previously unidentified colonies, bringing the known total to 61 and increasing global population estimates to 266,500–278,500 breeding pairs.

Some of the newly discovered colonies exist in offshore habitats or on ice shelves, something not previously reported for emperor penguins, leaving them particularly vulnerable to climate change.

With your support, we’re contributing to a larger project to buy and study satellite images to build an Antarctic-wide view of emperor penguin colonies over an extended period.

This will allow us to create a baseline that will help us understand how the locations and sizes of the colonies change from year to year. Specifically, we’re funding analysis of a large quadrant that hosts 16 known colonies.

© FRITZ PÖLKING / WWF

“The results of this study will contribute to three objectives,” explains Rod. “First, it will help us better understand emperor penguin population trends. Second, it may inform where marine protected areas should be established around the Southern Ocean, to safeguard foraging grounds. And third, it will help us to develop a dedicated action plan, potentially including specially protected designation, for the emperor penguin.”

Thanks to your support, we’re developing a clearer picture of the emperor penguin’s status, and of what the future might hold. In addition, all of us can play a part in tackling the biggest problem facing this species and other vulnerable wildlife: climate change.

“The wider issue is that only human action can secure the fate of this iconic species,” Rod concludes. “It comes down to global climate policy to safeguard the future of the emperor penguin.”

Be a penguin pal

Help support projects to monitor and protect Antarctic wildlife from the effects of climate change by adopting a penguin.