A steady eye looks down on a river deep in the Amazon rainforest. Staying 20 metres above the water, holding its course, it never blinks, sees everything, misses nothing. An hour later, it descends to join three people in a boat. Days, weeks or months later, a scientist in an office sees what the drone’s eye saw, gasping in delight as a pod of dolphins breaks the surface.

In another office in Brazil’s capital, Brasilia, WWF’s Marcelo Oliveira, coordinator of the South American River Dolphin Initiative (SARDI), is struggling to be heard. The world’s attention is on the Amazon rainforest, but its focus is on the trees. Marcelo has spent much of the past five years afloat on the great arteries of the Amazon and the capillaries of its tributaries. And he knows what is happening beneath the surface.

When WWF published our Living Planet Report 2020, the statistics it revealed were truly shocking – it showed that 84% of global freshwater species populations have been lost since 1970.

For the Amazon, we are approaching ‘situation critical’. This river, and others in the Amazon basin, are being polluted, poisoned and plundered on a scale never seen before. As Marcelo says: “We keep talking about deforestation and not about degradation.” Marcelo speaks out, but how can he get people to listen?

© GETTY IMAGES

King of the river

Dolphins enjoy an exalted position in South America. These most visible of river inhabitants feature strongly in the mythology of Amazonian tribes, and by declaring them ‘freshwater ambassadors’ Marcelo is hoping that some of the magic will rub off. Dolphins are at the top of the food chain: they are a simple barometer for the health of a river. If dolphins are thriving then all is well beneath the surface.

Dolphins have always swum throughout the rivers of the Amazon basin. They divide broadly into two types: the tucuxi (or ‘grey river dolphin’) species is closest genetically and in appearance to typical dolphins of the ocean, while the narrow-beaked Amazon and Bolivian river dolphins (also known as ‘pink river dolphins’ or ‘botos’ and ‘bufeos’) have evolved special features, most notably a raised forehead packed with sonar capabilities, enabling them to locate prey in murky, turbid water.

Even their dentition is adapted: sharp front teeth for impaling fish, and molar-like back teeth for grinding armoured catfish, crabs and turtle shells. But evolution can’t keep pace with human ingenuity. Our ability to exploit the rivers threatens the dolphins’ very future.

In November 2018, scientists at the IUCN acknowledged their parlous position by classifying the river dolphins as endangered. What has gone wrong?

Two major factors have precipitated a growing crisis. The first represents an ignorance of (or disregard for) how a river works. Governments of the Amazon have welcomed foreign investment in huge infrastructure projects to build hydroelectric dams, with damaging consequences.

“There is no consideration for the need for a natural river flow, for the people who live there or for the fish that migrate up and down rivers to reproduce and are essential to sustain livelihoods,” says Marcelo. “Dams can make populations of river dolphins simply vanish.”

Meet the dolphins

Tucuxi

Sotalia fluviatilis

A diminutive torpedo, the tucuxi has the classic marine dolphin shape, though this bluish-grey animal is half the size of a bottlenose. Tucuxi are highly sociable, travelling in groups of 10 to 15, and playful too, sometimes leaping exuberantly out of the water. They live throughout the Amazon and Orinoco basins.

Amazon river dolphin

Inia geoffrensis

Long beaks, bulbous foreheads and a pinkish hue give the world’s largest river dolphins an unusual appearance. Hunting by sonar in the dark, they’re unique among dolphins in being able to twist their heads from side to side to navigate through the roots in flooded forests.

Bolivian bufeo

Inia boliviensis

Only location and a winning smile separate this dolphin from its Amazon cousin. The bufeo is found solely in rivers in Bolivia. The one noticeable difference between the species appears when they show their teeth – the bufeo has more. Just like its close relative, its body colours lighten with age.

Satellite tagging of 35 river dolphins has sharpened our knowledge of dolphin behaviour and our understanding of just how badly dams affect these animals. These dolphins range far more widely than we ever appreciated, seeking shallow waters for mating, and following fish on long migrations towards their spawning grounds. Once rivers are blocked, fish cannot breed (impacting the local people who rely on them for food and income) and dolphin populations become isolated.

Half of the planned dams have now been built, and if all 277 come to fruition there will be only three free-flowing river tributaries left in the Amazon basin. It promises nothing short of an environmental catastrophe.

Other factors, a list of woes, pile yet more pressure on. Dolphins are used as bait to catch a profitable species of catfish, supplying markets around the region, and are sometimes accidentally caught in fishing nets. Overfishing by humans may be reducing food for the dolphins. And deforestation causes exposed soil to wash into the rivers; some of this silt contains traces of naturally occurring mercury, adding to the toxic soup.

Riverside cattle-ranching may be polluting the water even more. Marcelo predicts that if nothing is done to address all of this, if we stay with ‘business as usual’, in 50 years’ time the Amazon’s river dolphins will be heading towards extinction.

We’ve been here before. In the great rivers of south-east Asia, the world’s other river dolphins are ahead of the Amazon in charting a precipitous decline. Amazon dolphins number in the thousands; Asia’s are a fraction of that. We’re taking steps through a truly collaborative approach to make sure river dolphins in South America don’t suffer a similar fate.

The true cost of gold

Another threat, insidious and frightening in its consequences, has come to the fore: gold mining in the heart of the Amazon. This had been a growing concern, and now with a global boom in the price of gold, illegal mines are increasing. They lay waste to the land, blasting down to bare rock to leave a legacy of moonscapes.

These mines use the cheapest and easiest material for extracting gold – mercury, one of the six most poisonous elements on the planet. A WWF report found evidence of a largely nefarious trade in mercury filtering into the Amazon from Mexico. Mercury leaches into rivers, poisoning not just fish but also the dolphins and people that eat the fish. Every single dolphin we’ve tested so far has been found to be contaminated with mercury.

There are safer alternatives. Gold mines don’t need to use mercury in their processes. But as long as the product sells, and no distinction is made between legal and ‘poisoned’ gold, the illegal trade will continue.

On the other side of the Atlantic, WWF’s Karina Berg lives in a country that is a major driver in this despoiling of the Amazon basin. That country is Britain. “The UK is one of the biggest importers of Brazilian gold and currently we have no way of knowing its source,” says Karina, regional manager for Latin America.

“There should be safeguards and criteria in buying, or standards for production and importation. That’s where we must support conservationists working on the ground in the Amazon.”

Beneath the surface

Here are five fascinating facts about the Amazon’s dolphins, revealed by our satellite tagging

MALES ON THE MOVE

There’s a marked difference in movements between the sexes. Female dolphins travel less, perhaps due to pregnancy and care of offspring. Males range more widely, often in search of females.

FOLLOW THE FISH

The type of water affects how far dolphins travel to find food. Rivers with high sediment levels are more productive so dolphins here travel less than those in waters which are lower in nutrients.

SOCIABLE SWIMMERS

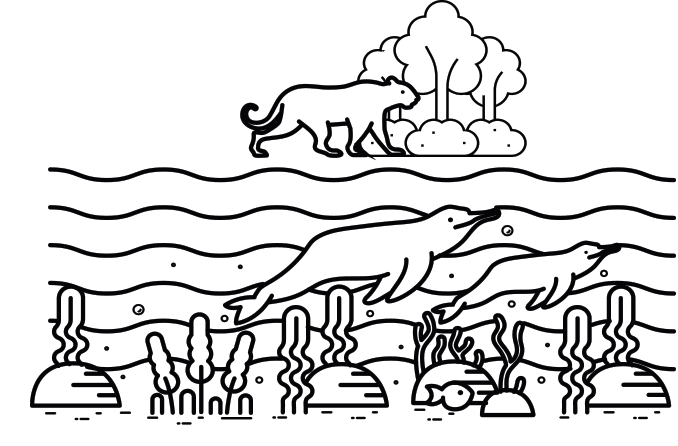

While the big cats on the riverbanks hunt alone, river dolphins are anything but solitary. They are recorded moving up and down river in what are likely to be big family groups.

FLOOD OPPORTUNISTS

Ordinarily, dolphins stick to the main channel of rivers, but when high waters cause adjacent forests to flood, dolphins are quick to take advantage by swimming into these temporary feeding grounds.

HOME RANGERS

Dolphins’ home ranges are far bigger than those of other large mammals of the Amazon. Their territories are twice as large as that of a jaguar and four times as great as the secretive tapir.

Working together

In the summer of 2020, the International Whaling Commission – the scientific body responsible for regulations relating to cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises) – agreed a conservation management plan proposed by the governments of Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. This crucial act of collaboration was largely driven by the efforts of WWF and other NGOs, under SARDI.

Having an accurate picture of river dolphin populations is key to informing conservation measures. Over the last 15 years, institutions have carried out expeditions to estimate river dolphin population sizes in the range countries. Around 47,000km have been covered during 42 surveys of at least 45 rivers and their connecting lakes, tributaries and channels.

As well as supporting some of these, we’ve helped consolidate all the data in one place and, for the first time, we have intricate population distribution maps for river dolphins across the Amazon. With this we can now set out conservation aims and achievements for this amazing species.

The next few years are critical because, as Marcelo points out: “We still don’t have a real number for river dolphins. We only have studies showing population decreases in certain areas. We need a baseline so we can say: this is where we are. Evidence showing populations and where the threats are likely to lead to the most impact on dolphins will enable us to prioritise our action.”

Technology is on our side. Researchers have begun using drones, the eyes in the skies, as a cost-effective method of monitoring river dolphins. Developments in thermal imaging mean that drones will be able to work at night, too.

Before long, we will know the scale of the task ahead. In the meantime, Marcelo and SARDI’s team work a charm offensive: “When we talk to people about river dolphins, we’re trying to build a narrative about the importance of healthy species and rivers to people’s livelihoods and wellbeing. Cooperation between countries is key, as rivers and wildlife do not recognise borders.”

Read more about our work through SARDI.

More to explore

You helped us discover more about pink river dolphins

An expedition in Colombia, made possible thanks to your support, has helped us learn more about pink river dolphins and how to protect them