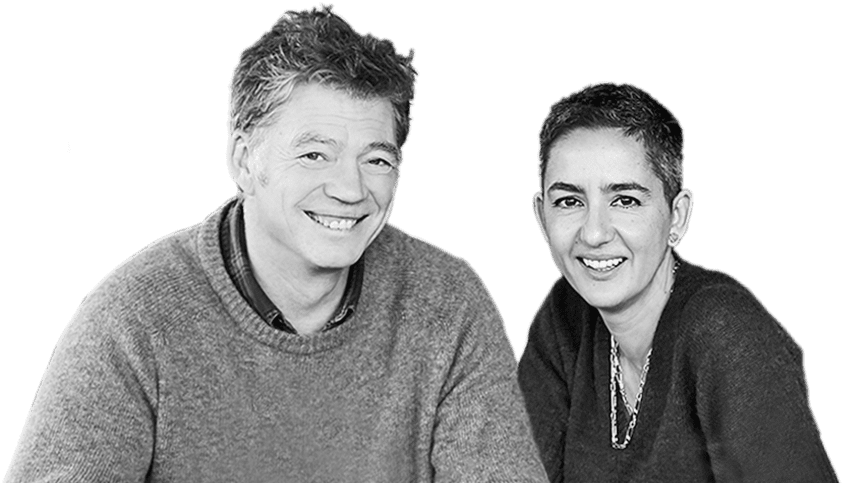

Food pioneers Guy and Geetie Singh-Watson are perhaps best known as – respectively – the founder of Riverford, the organic farm and vegetable box delivery company, and the ethical restaurateur behind the UK’s first organic pub.

Guy, a WWF ambassador, began converting his family farm in Devon to organic practices in 1987, and in the 1990s he set up one of the UK’s first veg box delivery services as a way to distribute his produce. Today the company has organic farms around the UK and France, and works with other organic growers in Europe.

Geetie opened The Duke of Cambridge – the UK’s first official organic pub – in north London in 1998. This was followed by a further three organic pubs in London and, most recently, The Bull Inn in Totnes, Devon.

Geetie, what prompted you to open an organic pub?

Geetie When I started working in restaurants I was disillusioned by the lack of thought about any form of environmentalism, from the food procurement to how they were dealing with waste. I realised that there was a market for people like me who wanted to eat out but feel they were having a positive impact. So in 1998 I opened the first organic pub in the world, The Duke of Cambridge in north London.

What exactly does the term ‘organic’ mean?

Guy The simplest definition is food that’s grown without the use of synthetic pesticides and fertilisers. But it’s much more than that – it’s working in partnership with nature, rather than wanting to suppress it.

We’ve become so divorced from the seasons and I think the main driver of that is the retailing model that we have in the west, which is that a supermarket feels like you’re going into a hospital – it’s sort of aseptic, it has no relationship to nature.

That divorcing of what happens in the kitchen from what’s happening in the fields has really driven the loss of seasonality, which has driven so much of the environmental impact of our food. People fail to make a connection between what they’re eating and its environmental impact.

Geetie You need to think about the impact of absolutely everything you’re doing. And food is so essential to this. And what I want to try and do in the pubs is teach people that it can be as delicious. You just change a few things, and you can really change the impact you’re having on the planet.

© DAVID BEBBER / WWF-UK

Do you think there’s more that can be done within the farming industry?

Guy Agriculture is contributing between 10-50% of global emissions, and probably more in terms of biodiversity loss, so it’s huge. Can we do more to produce the food we need with less impact? Most definitely. Some of the most inspiring agriculture I’ve seen has been with small-scale farmers in Uganda who have incredibly complex farms, growing 50 different crops in close association with each other, using specific plants to repel certain insects. Those farmers are real ecologists.

What could the UK food industry do to replicate the success of those Ugandan farmers?

Guy More diversity, which is difficult when one farmer – statistically – has to feed almost 200 people. Inevitably this requires a lot of mechanisation, and that pushes us towards monocrops, which is bad for diversity. But with new technologies we could get much more diversity back in the countryside.

We can use our better understanding of soil ecology to find ways of growing food with less soil disturbance, which is the cause of soil erosion and polluted rivers. That means looking for perennial rather than annual crops.

An annual crop has to be grown from a seed or tuber every year and requires removal of any other plants in competition, but a perennial plant is there all the time, like a tree that generates nuts or fruits every year. The key is that it doesn’t involve cultivating the soil and creating a seedbed.

Geetie I think seasonality is the most important aspect of it. If we stopped expecting constant access to all types of produce, we’d reduce that global market very quickly. But more importantly, we would enjoy food more. If you just have peppers in summer, they’re heaven because you’ve been waiting for them all year.

Guy Our choice has to be between things which are sustainable, not between tomatoes in one supermarket or the other.

Organic produce can be more expensive to buy. What can people do if they can’t afford it?

Guy Eating less meat and fewer animal products is a great start. But it’s really important that those people who have the money to buy organic, do so. That then drives the market, and the change, because when more is sold prices come down. It’s imperative that the people who have that wealth use their power in a more responsible way.

The wild is calling. It’s time to act.

To hear the full interview with Guy and Geetie, subscribe to our Call of the Wild podcast, hosted by WWF ambassador Cel Spellman. Just search for Call of the Wild wherever you listen to podcasts, or visit our Call of the Wild site.

More to explore

Video: How to change the future of our food

The food we eat has a huge impact on nature, but individuals and industry can change this. We asked farmers and food experts for their views on the future of food