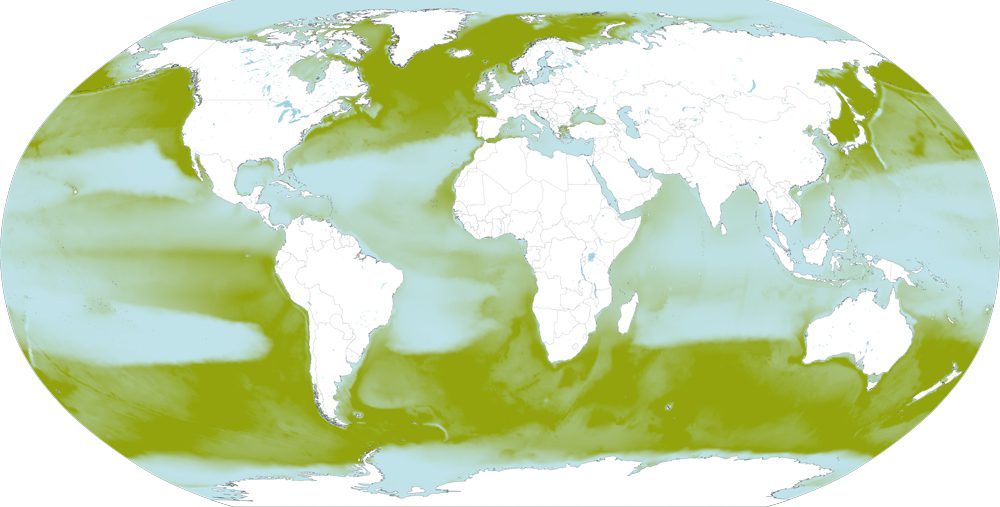

A thousand years after Viking seafarers named the ocean the ‘whale road’, WWF and marine scientists have laid out a new map of the planet. It could be a motorists’ atlas, thick bands representing motorways, thinner strings the connecting A-roads.

Except that every road has a blue background. These are the marine superhighways along which the world’s largest whales migrate. And they do so at huge risk.

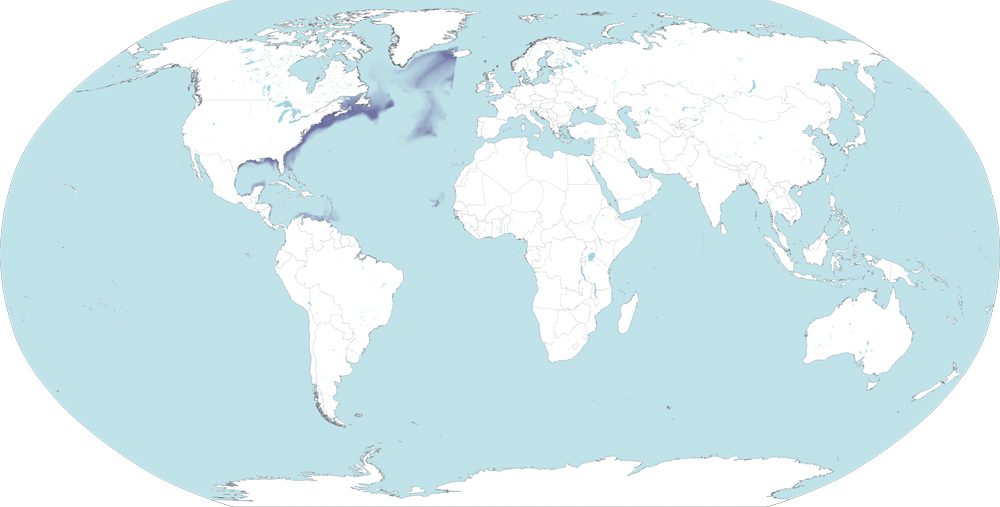

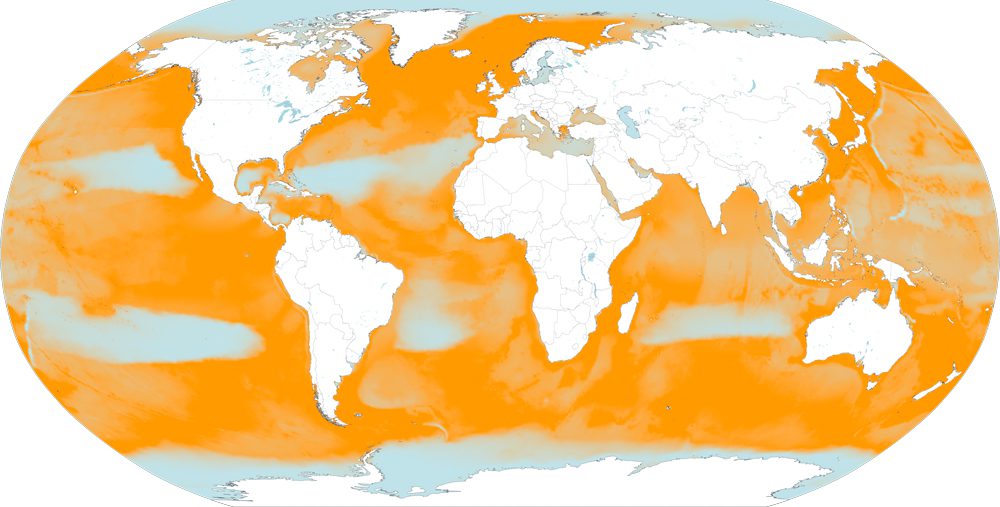

The routes on our map were created from data gathered from more than 1,000 whales. They were tracked by satellites on journeys taken over 30 years using data supplied by more than 50 research groups.

And what journeys! The great tails of baleen and toothed whales power them across enormous distances to find shifting sources of food. A giant humpback migrates from polar seas to the tropics and back, covering almost as many miles as the circumference of the Earth in less than two years.

Whale roads

Different places are important at different times of the year for different things; perhaps a seasonal bounty of zooplankton, or a nursery for the young. The track of each individual is plotted by a thin line – the thickness of the bands testifies to the consistency of the paths taken by so many whales.

This migration map is a vital part of a new report, Protecting Blue Corridors, which provides a comprehensive look at whale migrations across all oceans.

It reveals how whales are encountering multiple and growing threats from human activities in their critical ocean habitats – areas where they feed, mate, give birth and nurse their young – and along their migration superhighways, or ‘blue corridors’.

© GETTY

A collaborative analysis by WWF and leading marine mammal scientists from Oregon State University, the University of California Santa Cruz and the University of Southampton, it describes a situation that has become perilous.

Humankind’s rapacious exploitation of the world’s oceans has led to six of the 13 great whale species being classified as endangered or vulnerable, even after decades of protection.

Approximately 300,000 cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises) are killed each year as a result of fisheries bycatch – entanglement in fishing gear such as nets and lines. Still more are snared by ‘ghost gear’ – the discarded, lost or abandoned fishing gear that litters the sea.

One of the world’s most endangered species is the North Atlantic right whale, with just 335 individuals surviving. And 288 of those animals appear to have been caught in fishing gear at least once in their lives. How many more died unnoticed?

Attacked from all sides

There’s a frightening crossover between whale superhighways and shipping lanes. Traffic rose fourfold between 1992 and 2012, and the rate is increasing. And there’s only one winner in a collision between a whale and a 500,000-tonne supertanker.

Extra sea traffic, seismic surveys, military sonar and industrial activity, such as drilling for oil, have all contributed to underwater noise levels doubling each decade since the 1960s – a catastrophe for animals that have evolved to use sound as their primary sense.

Unable to hear or vocalise over this din, whales are deprived of their ability to communicate over tens or even hundreds of miles. What’s more, as climate change heats the ocean, it’s causing shifts in both abundance and distribution of prey.

Add the scourge of toxic chemical contamination and plastic pollutants filling their stomachs uselessly, and it’s easy to understand why whales are in such grave danger. So what can be done?

Travellers on the blue corridors

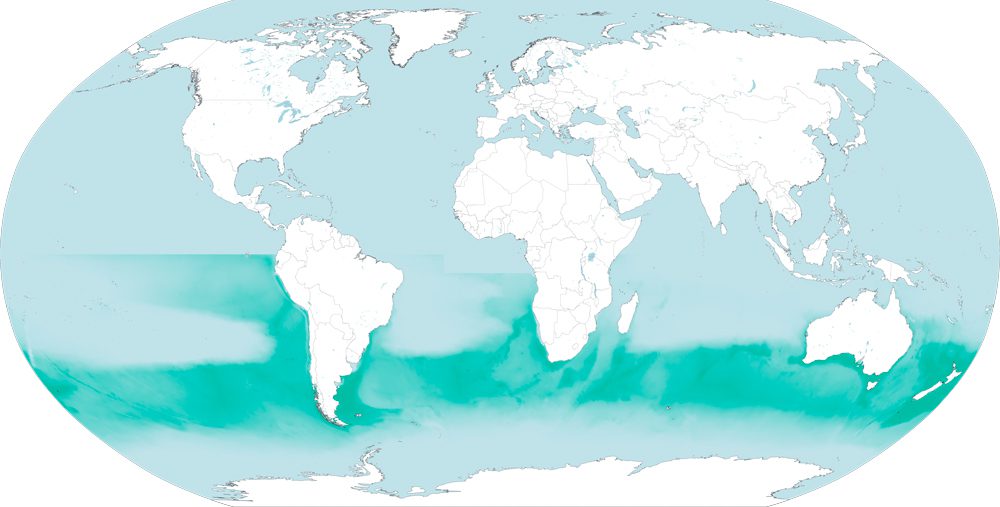

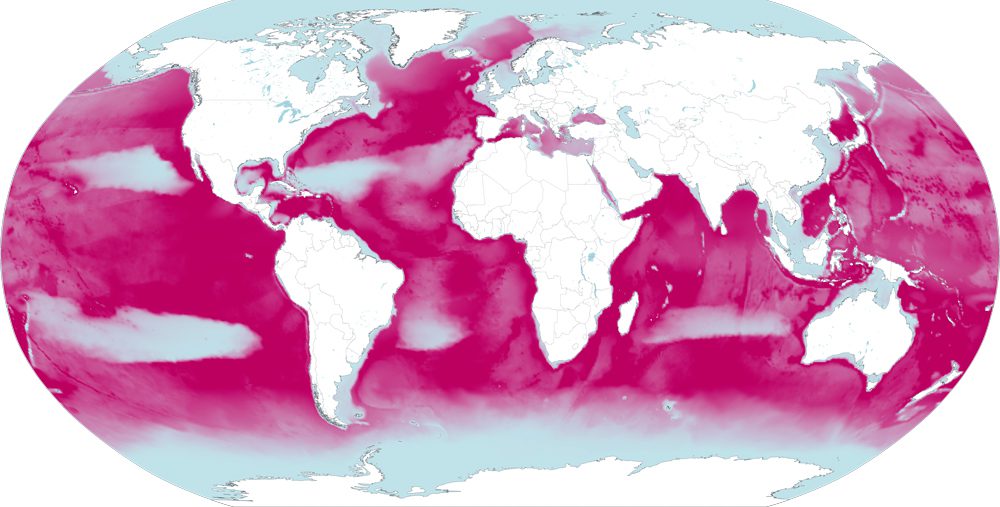

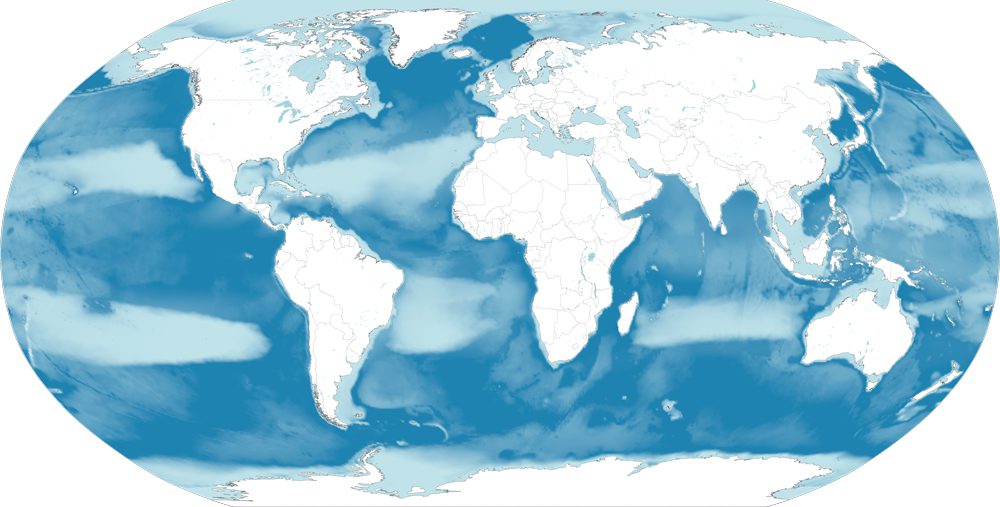

Whales move across ocean basins as they travel between feeding and breeding sites, in and out of international and national waters. Some migrations are seasonal, some are year-round. Using data from over 1,000 tracking tags, marine mammal scientists have mapped the habitats that are crucial for various species, and the routes travelled between them.

FIN WHALES

(Balaenoptera physalus)

IUCN Status: Vulnerable

Length: 17-20m

Population: ~100,000

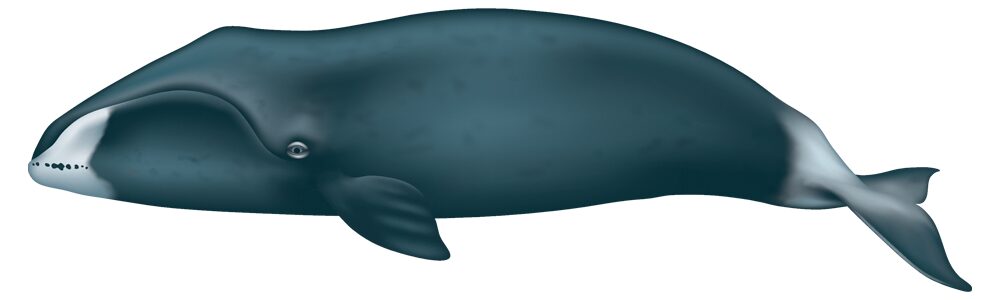

BOWHEAD WHALES

(Balaena mysticetus)

IUCN Status: Least concern

Length: 13-15m

Population: ~10,000

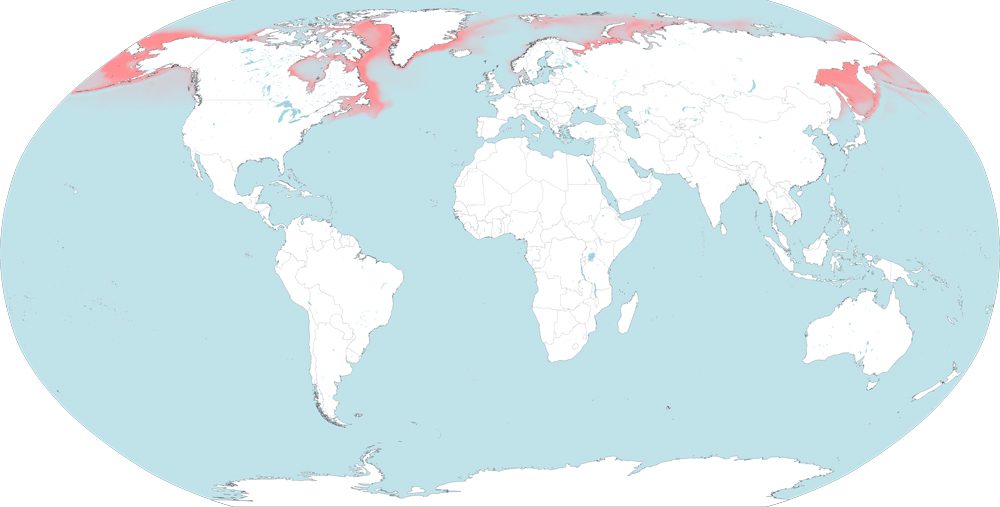

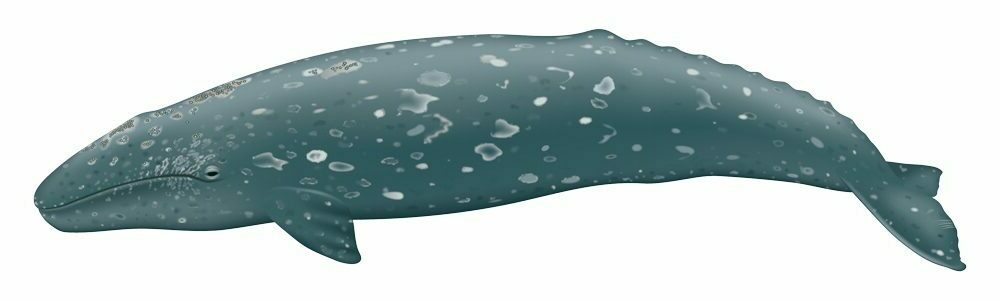

GRAY WHALES

(Eschrichtius robustus)

IUCN Status: Least concern

Length: 12-4m

Population: ~27,000

NORTH ATLANTIC RIGHT WHALES

(Eubalaena glacialis)

IUCN Status: Critically Endangered

Length: 13-16m

Population: ~350

HUMPBACK WHALES

(Megaptera novaeangliae)

IUCN Status: Least concern

Length: 13-16m

Population: ~84,000

SOUTHERN RIGHT WHALES

(Eubalaena australis)

IUCN Status: Least concern

Length: 15-18m

Population: ~13,600

SPERM WHALES

(Macrocephalus physeter)

IUCN Status: Vulnerable

Length: 11-20m

Population: ~350,000

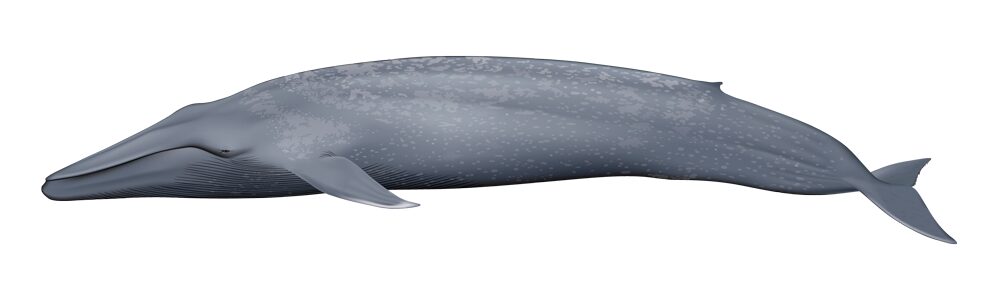

BLUE WHALES

(Balaenoptera musculus)

IUCN Status: Endangered

Length: 24-26m

Population: ~5,000-15,000

“We can protect the critical habitats where whales feed, breed and mate, but they still must migrate past obstacles and threats to get to those places,” warns WWF’s chief marine adviser, Dr Simon Walmsley.

“If we’re trying to protect humpbacks, it’s no good focusing on the Arctic or the Antarctic and doing nothing about their migration route in the middle. Any network of protected areas must not only consider critical areas, but also the pathways between them – and that requires international cooperation.”

Marine protected areas, such as those in UK waters, do offer legal protection, though we’re still pressing for proper management to render them effective. But on the high seas, outside the jurisdiction of any nation, whales lack rights of passage. Across an astonishing 42% of the planet’s surface, wildlife has no overarching legal protection whatsoever.

All this may be about to change. Patient cooperation between governments backed by conservation groups is bringing an international United Nations treaty – the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction Treaty – close to fruition. This agreement will oblige all states to act.

Protecting the high seas

“It’s a game changer,” says Simon. “There are currently no ways of establishing universally recognised marine protected areas in the high seas. The UN treaty will enable us to draw together all activities on the high seas, examine their impacts on biodiversity, and suggest measures that will help protect it.

“As a shipping superpower, the UK has the opportunity to show international leadership – and our new report will inform the process. It will take time, but we can deliver a robust mechanism for establishing globally recognised networks of high-seas marine protected areas.

“And there are little things we can do now that, if applied globally, will have a huge effect. Nets can be fitted with sonic pinger-alerts that steer whales away from danger, and all nets could be tagged by law, so that discarded gear is traceable to the ship that dumped it. The technology exists for us to use modified ropes that break if a whale gets entangled.

“And ships could slow down. A slower ship makes less propeller noise and uses less fuel. They can also change course to avoid whales – the more data we have, the better the chance they have. A long voyage may take more time, but surely it’s worth it.”

In 2023 we’ll see the 50th anniversary of a UK ban on whale imports, a move we were instrumental in bringing about. Previous generations fought to prevent cruelty to these intelligent beings. Today, we know there’s another compelling reason why we must protect whales: each animal absorbs huge amounts of carbon, locking up as much as thousands of trees over its lifetime.

When it dies and settles in the sediment for millennia, the whale gives a parting gift to the planet.

Their future is in our hands and our future is in theirs.

More to explore

Drowning in sound?

Our oceans are alive with an orchestra of marine wildlife. But as the ice melts, the harmony of Arctic seas is being drowned out by human activity. We’re working to understand the impact of this audio intrusion – and how to help combat it